Uniquely Me: A Workbook

Book / Produced by Individual TOW Project member

Chapter 3: Discovering Your Own Story

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsEvery time a person does something that they experience as enjoyable or satisfying and done well, they reveal a certain pattern of behaviour. That design is unique to the person; no one else has one exactly like it. It is like a fingerprint. (Arthur Miller)

This chapter marks the beginning of our workbook. Here is where we turn from principles to practice. We are inviting you to an exciting opportunity – nothing less than examining your own life and how you live it!

We’ve already quoted Paul’s words in Ephesians 2:10. Look at them again, and see what a remarkable insight they give about what God is up to in our lives:

“We have been shaped by God, created in Christ Jesus, to do good works, which God has prepared for us.”

God has designed our “shape”! If God has constructed each of us to a unique, individual design, then we need to know as much as we can about that design. It should tell us a lot about the work we are best fitted to do.

So how do you get a clearer picture of what your shape looks like? And how do you see what kind of “good works” this shape points you towards? Or to put it another way, who exactly are you?

If you had lived in an earlier generation you would probably have found it easier to establish your identity. Who am I? I am a blacksmith … or a shepherd … or a tailor. Why? Because that’s what my father was. Who are you? I am a wife and mother. Why? Because I was born a woman and from my childhood I expected that marrying and raising a family would be the whole focus of my life.

If you’d lived in the past, you would probably have followed in Mum or Dad’s footsteps. And if that avenue was closed you would no doubt have accepted your parents’ guidance. Wayne’s mother, who really wanted to be a dressmaker, was instead found a job in a bank by her parents when she left school. For most people, there was little choice. Fewer opportunities were available. And what there were, were usually decided by the family and tradition that a person belonged to.

Nowadays our society offers us vastly more options, and vastly greater freedom in pursuing them. That, of course, just makes our decisions all the more difficult! The responsibility to find the right vocation can sometimes feel overwhelming, especially for Christians who want to feel that they are doing what God wants them to do.

In this chapter, therefore, we offer you the opportunity to look at yourself, to picture your “shape”, to see what you were designed for, and to identify a future (or a new direction) that will enable you to live out the kind of life you want. How’s that for a grand aim! Grand it may be, but it’s not too much for the person that God wants you to become.

Your personal history

We are each given a limited number of years on this planet. Many people just drift through those years, doing whatever comes to hand. But is that enough? Are there ways we can be more pro-active, preparing ourselves to make good choices? To what extent does God invite us to influence or choose the course of our life? Can we ask God to help us sort through and understand just what it is that we do best, and therefore what it is that we should concentrate on?

It’s our conviction that we can … and should.

But how do we catch a glimpse of the future? We believe that the best place to look for clues about your future, is actually in your past and the present. Rather than speculating about what might one day be, we think it’s best to focus on your personal history (however short or long that has been) and on what you are doing now. Why? Because only then can we really look carefully at hard data that is specific to you.

Only in this way can we be sure, when later we start to use some tools borrowed from other people’s schemes and stories, that we started with you. That we took seriously the evidence that comes from your life. The exercises you do throughout this book will depend for their usefulness on insights gained in this chapter.

Our purpose, then, is to help you identify what you do best, what satisfies you, what gives you fulfilment. When you lie down at the end of the day and look back over all its many activities … which moments are the ones that you recall with the greatest pleasure? When you look back over your life, which are the activities that you value most? What are the tasks you have attempted and jobs accomplished that have given you the richest sense of satisfaction – not only in the finishing, but also in the very doing of them?

But before we rush into this exercise we invite you to stop and reflect for a moment.

Think about your present life situation. Be clear in your own mind that God is with you in what you are doing right now. Where you are at this time in your life is intimately connected with God's purposes for you. This does not mean that you must stay where you are, but it does mean that you must not feel you need to be somewhere else, or be someone else, before you can be part of God's purposes.

Some people battle with the belief that their lives are in the wrong place. If that is a problem you face, our advice is that you begin by giving up fighting who and where you are, and instead embrace the present as God's opportunity to lead you into his future.

The present is where you have to begin. Only after coming to terms with that, will you be truly ready to put effort into understanding what you can learn about yourself from systematically examining your past.

This involves remembering and retelling significant parts of your own story. As you do this your aim is to gain a picture of your shape. To understand how God has wired you, and what journey you have travelled that brings you to where you are now. Seldom is the future God has prepared for us completely divorced from our past. Although there may be changes ahead, it is still essentially the same person we take into the future. And although there may be some things that God is inviting you to leave behind, you need to understand the essence of who he has made you to be, in order that more of the God-given potential he has placed within you might be realised.

Both in your creation and through experiences, God has gifted you. He has done this so that you can work with him and fulfil his purposes by giving full expression to the potential for doing good that he has placed within you. In this chapter we want to help you catch a clearer glimpse of what that potential looks like. You will do it by trying to understand how parts of it have begun to be expressed and realised already, sometimes without your even being truly awake to it … because your central core will seek to express itself in everything you do, even when it feels that the work you are involved in doesn't fit.

The aim, then, of the following exercise is to remember some of the most satisfying accomplishments from different periods in your life – those activities that gave you a buzz because you felt you had made a contribution of real worth, or because you were doing what you really enjoyed doing and were good at.

Note 1: Before you set out on the exercise, read through all the instructions so that you gain an overall idea of what to look for.

Note 2: Although this exercise requires time and effort, it’s worth it. It will lay foundations and will make other exercises in later chapters easier to work through. If you want to know more about this approach, the exercise draws on the insights and work of Ralph Mattson and Arthur Miller, as found in the books Finding a Job You Can Love, The Truth About You, and Why You Can’t Be Anything You Want to Be.[1]

Your Autobiography

Step I

We want you to choose the seven most satisfying events of your life – times when you achieved something especially pleasing (not just pleasing to others, but specifically pleasing to yourself), when you really enjoyed what you were doing, and when you gained a sense of fulfilment in what you achieved. These should focus on what you helped to make happen and not just be enjoyable events that others organised for you.

There are several ways of going about this. Use one or more of the following:

You can divide your life up into a number of blocks starting from early childhood. Quickly list all the most significant things you enjoyed doing in each period.

You can think back over the most pleasurable experiences of your work, your play, and your learning. Write down the most memorable.

You can make a list of the different roles that you have played in your life.

Now look back over what you have listed. Choose the seven most satisfying and enjoyable achievements overall. You may wish to include some that are long-term accomplishments, rather than separate events. (For example, becoming proficient in some activity like fishing, or mathematics, or a musical instrument, or basketball, or truck driving…) Whatever you choose, the common denominator is that sense of satisfaction, that feeling that this is something you were created to do … and you do it well.

Step II

Write a detailed description of each of these seven achievements under the following headings.

A one-line summary of what you did.

Details about what you did, clarifying exactly how you personally went about it.

Go back over what you have just written and underline the verbs you used to describe personal actions that gave you satisfaction. (For example: “I drew up a list of jobs that needed to be done. Then I collected the tools/equipment needed for those jobs. I asked individuals to take responsibility for one task…”). Also underline nouns that describe what you particularly enjoy working with.

What aspects of this activity gave you most personal satisfaction?

Step III

Read back through what you have written and try to answer the following questions about themes that keep on recurring: (You don’t need to restrict yourself to the words listed here. They only provide examples.)

1. Abilities: What abilities were you using to accomplish the results? Note down those abilities you exercised that keep on recurring in the majority of your stories.

Choose some from the list below or come up with your own descriptions.

Writing Analysing Persuading Strategising

Teaching Designing Negotiating Researching

Organising Evaluating Co-ordinating Networking

Counselling Creating Building Advising

Shaping Problem-Solving Improvising Investigating

Planning Assembling Implementing Learning

Motivating Experimenting Pioneering Entertaining

Promoting Publishing Performing Building Relationships

Synthesising Managing Operating Observing

Interviewing Communicating Training Mentoring

Write down the abilities that recur most often…………………………………………….

Annette

Five years into my career as an Occupational Therapist I was offered what was to me a dream opportunity. My brief was to come up with some kind of information package for Rest and Residential Homes in the community, helping them to establish stimulating recreation programmes for their elderly residents.

Six months grew into eighteen as I surveyed Rest Homes and interviewed management and staff to discover their needs. Then I researched and assembled the relevant information, packaging it into a handbook for staff. I followed this up by devising and running an introductory course to train staff, and then published that as well.

I thrived on being given the room to use my own initiative and imagination on how to approach the task.

I enjoyed being able to consult with people, using active listening, coaching, and teaching skills.

I enjoyed the research involved.

I was stimulated by the task of finding ways to communicate and package the information – and then putting it into practice, with the result of seeing people become better equipped.

I particularly enjoyed being able to choose how much time I spent with people. When I needed a break from people contact (pick the introvert!), I could spend time in research.

Searching for ways to improve the quality of life for elderly people in Rest Homes was a way to put my values into practice.

Looking back over the whole experience I now see that a number of these elements are recurring themes in my life.

2. Subject Matter: From working with what objects or subject matter do you receive most satisfaction?

Choose some from the list below, or come up with your own descriptions.

Ideas Money Numbers Concepts

People Tools Machines Colours

Designs Methods Business Schedules

Graphics Symbols Animals Procedures

Policy Projects Language Books

Budgets Problems

Write down the subject matter that recurs most often…………………………

3. Circumstances: What circumstances do you function in best? What circumstances are most positively motivating for you?

Choose some from the list below, or come up with your own descriptions.

When working on a project

When you believe in the cause

When you are working on your own

When there is a clear goal

When trying to solve a problem

When you can see concrete results

When personal growth occurs

When meeting a need

When you are pioneering something new

When clear guidelines are given

When you have freedom to go about things in your own way

When a whole group or organisation is involved together

When a challenge or test is involved

When competition is present

When you are working to a deadline

When you can take as long as you need to

Write down the motivating circumstances that recur most often…………………………

Alistair

I thought I was going to be a missionary overseas, but it didn’t happen like that. While I was still a pastor I helped start a mission group with a special purpose. We aimed to mobilise western Christians to live and work among squatter inhabitants of a number of large Asian cities. As it happened I stayed home myself, but I got involved because I identified closely with the dream, and because I had worked closely with some of the young people who became members of the first two teams to Manila in the Philippines. I ended up working with this group for about 11 years altogether, the last four full-time. My role involved a lot of time away from home networking with churches and other agencies, offering pastoral support to workers and mentoring candidates in training. I was also helping to clarify the vision and values of the mission through exploring a combination of biblical roots, theological frameworks, community development theory and cross-cultural understanding. It was a very demanding time, but also one of the most satisfying experiences in my life. Some of the elements that made it so satisfying were:

I enjoy pioneering ventures. I am not a maintenance man.

.I like working as part of a team.

I love to encourage, equip and support young people to pursue their dreams.

I like travelling and teaching groups, but even more I enjoy personal mentoring in a continuing relationship on an action/reflection basis.

I find great satisfaction in both preparing people to undertake a project, and later helping them to evaluate what they have done.

I enjoy doing research and trying to find words to communicate important insights.

I yearn for Christians to develop a strong personal faith and social conscience.

As I look back at this and other similar experiences I’m aware that most of these are recurring themes in my life.

4. Operating Relationships: How did you relate to others to accomplish these meaningful results?

Choose one or two from the list below, or come up with your own descriptions.

Manager

Solo effort

Facilitator

Team leader

Co-ordinator

Motivator

Director

Coach

Team member

Write down the operating relationship that recurs most often…………………………..

Wayne

I’ll never forget the day I was asked to organise and plan a four day bus trip, taking 130 teenagers and leaders from Wellington to Auckland. My mind immediately ‘’got into gear”. Even while that first meeting was still in progress I was working out how I could make it successful! I was only 20, but I’d already planned and organised a similar event (on a much smaller scale) the year before when I was still a university student in Dunedin. I’d borrowed the idea (and name) from a friend up north, and developed the concept.

Called “Entertainment Plus”, the idea was to travel to another city and do as many fun things as possible. It involved me in investigating the possibilities, and negotiating bus hire, entertainment venues, and accommodation options. Then I had the challenge of scheduling all this (few of the venues could cope with three busloads of people at the same time), doing costings, promotion, etc.

I planned the whole event in detail – down to the last minute. And it worked like clockwork. Everyone had a ball – including me! Looking back, I can see a certain predictability in the way I went about it – predictable because it’s a pattern that has repeated itself countless times in my life since. Some of the factors were:

Rather than create the idea from scratch, I took the seed of an idea from somewhere else and saw the potential, substantially developing it as my own.

After initial encouragement and help from my supervisor in getting the project’s boundaries sorted, I firmly insisted on taking sole ownership of the project. I wanted a hands-off approach from my boss.

A number of values were very important to me. For example I rose to the self-imposed challenge of doing as many activities for the least amount of money. I also wanted kids to experience as many different new things as possible in the time.

I visualised what I wanted to see happen, then used my investigative skills, along with extensive pen-and-paper lists, charts and diagrams, to work out the scheduling of the whole exercise.

5. Results: What particular outcomes give you that pleasurable sense of accomplishment?

Choose some from the list below, or come up with your own descriptions.

Overcoming a challenge Solving a problem Achieving excellence

Seeing something built Completing a project

Fulfilling expectations Receiving thanks Knowing you helped

Learning something Ending up in charge Pioneering new ideas

Organising what was a mess Gaining recognition or influence

Write down the results that recur most often…………………………………………

Your Fingerprint

These factors combine together to give us that unique multi-dimensional motivational design Arthur Miller calls our motivational “fingerprint”. Discerning the shape of this “fingerprint” is a very important key to discovering our SoulPurpose.

Summarise what you have discovered from 1-5 above:

1. Abilities

2. Subject matter

3. Circumstances

4. Operating with people

5. Results

Feedback from friends: personal reflections in a small group

Here is your opportunity to gain from the encouragement of friends – and perhaps, at times, their wise caution! When you have worked your way through the material of this chapter, meet with your group. Take it in turns to present what you have discovered about yourself. Allow the group to affirm or question the understandings you have come up with, amplifying your own insights by offering their own observations of how you work best.

Allow plenty of time for this. You may need to give more than one session to this sharing, so that all members of the group can profit fully from it.

Some Barriers to Discovering our Giftedness

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsDoing the above autobiographical exercise and making your own analysis will be easier for some than others. Many of us, for a number of reasons, have lost touch with our sense of what we really enjoy. It seems incredible to say that, and yet it can easily happen. Here are some reasons…

We have pursued interests and developed skills according to early influences on us.

Our parents, teachers and other significant people gave us messages that had some degree of bias:

- The mum or dad who wants a child to succeed to the family business... It’s all too easy for parents to selectively encourage their child whenever he or she shows any relevant talent or gifting – and at the same time to ignore or neglect those talents/gifts that don’t fit the mould, even if they are stronger.

- The mum or dad who wants a “chip off the old block”… In the same way, parents may selectively encourage the interests in their child that match their own, ignoring those that don’t.

- Caregivers can easily have biases about what is a good job and what isn’t, with no regard for “fit” between a person and a job.

- The mum or dad who missed out. Dad wanted to be a pilot, but never received the encouragement or resources. Now he is encouraging his son to do so, fulfilling his own ambition rather than his son’s.

This is not to say that as a parent or teacher you should not provide any kind of encouragement or guidance for your children. You should certainly help them find their talents and interests. But you should also be aware of your own biases. You need to learn to “read” your children. The key positive response to look for is enthusiasm. What is it that your child loves to do?

We have received messages that undermine the value of those things we really enjoy:

- The child wants to do creative “work with their hands”, but Mum and Dad think the real money is to be made in working with figures or computers. So they’re steered away from natural interests.

- Or the opposite. Children sometimes positively want to follow in their parent’s footsteps, but all Mum and Dad can see are the obstacles that they themselves faced along the way, or their own disillusionment. So they try to discourage their child.

We have been influenced by stereotypes:

- The woman who has an administration or leadership strength … but she chooses to ignore this because she has been taught or believes that leadership is a man’s job.

- The man who wants to work with children … but is afraid of being ridiculed for taking on a “nurturing” role.

- “All lawyers are money-grabbers” … so a young woman steers away from a career she could have made a difference in.

We have developed competence in areas that don’t necessarily match our own desires.

In conscientiously rising to meet a certain need we have developed areas of competence that we become known for. Before too long we find ourselves being type-cast into certain jobs, just because we showed we could do them:

- Like the woman who takes on the job of treasurer for an organisation when she really longs to be involved in training volunteers… She is competent at handling the finances but she really wants to be involved elsewhere. Even when she joins other organisations she finds herself asked to offer her services as treasurer.

- Or the young father who regularly solves technical and computer problems for his friends, but really wants to be outdoors doing something physical.

What others think takes on too much importance:

- Some people have been raised to believe we should defer to others for all our major decisions. They surrender the responsibility of their own life to those who they think will know better than they do. While others often have helpful advice and information for us, this should be weighed up against what God has revealed to us about who we really are and what we can do with our lives.

- We can become so caught up in what others want of us that we lose sight of what we enjoy.

We have bought into the belief that if it feels good there is no sacrifice on our part:

- Enjoyment has had a “bad rap” with some Christians. They think that the less they like something, the more they should do it – so they will grow in obedience and submission.

The truth is that any job/role/career will bring challenges and demands that stretch us to new growth. Yet if we enjoy what we do, we would be able to so much more effectively express who we are, and grow spiritually at the same time. Yes, there are times when we need to do tasks which don’t particularly match our Fit. Does it make us more spiritual if most of our life seems taken up with these roles? Absolutely not. God has made us for a purpose. A car manufacturer doesn’t design a heavy duty 4WD for use on sealed roads – though it will drive perfectly well on them. It’s built for the off-road. That’s where its unique design will most find expression. So it is with us.

So it’s important to:

- Relish those activities that you really enjoy, that energise you, and that you find fulfilment in.

- Look for clues. As a child what activities did you naturally gravitate towards? What was your favourite play activity, or a play activity that set you apart from most people? Examining your play activities is a good place to start because it usually points to what it was you loved to do and may be a good indication of your own longings. There’s another reason for looking at your childhood. Parents didn’t always associate your play choices with a likely future career and were more likely to leave you to do what you excelled in.

- Identify the voices that try to influence you, and ask God to help you sift them. Pay attention to what you thought or felt about a particular option, not what others thought. Realise it may take time. Sometimes we have made a lifetime habit of taking on activities, jobs, and even careers for the wrong reasons, some of which are listed above. It can take a while to re-connect to the person God created you to be. Commit your future direction and your searching to God, and trust that He will provide the clues you need to keep moving forward. Remember: “Don’t neglect the gift that is in you…”

Chapter 4: Unraveling Our Personality

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsIf you have anything really valuable to contribute to the world it will come through the expression of your own personality, that single spark of divinity that sets you off and makes you different from every other living creature. (Bruce Barton)

We’re all sitting in front of the TV. Excitement is mounting. It’s an international rugby test match. The scores are tied and we’re in the final moments of the game. Our winger receives the ball twenty metres out from the goal line. He swerves past one player, runs right over another and dives over the line just as the opposition fullback tackles him.

It’s a try! The game is won. Everyone in the room goes crazy and begins to celebrate. Tony jumps up in the air, punching the air with his fist. Sue screams with delight. Michael just sits there with a huge beaming and relieved smile, nodding his head in approval. Gemma strains her head to see the action replay, while Jeremy and Alan begin to talk excitedly about the lead-up to the try, analysing which players created the space to allow the giant winger to crash over in the corner.

Six people in the room. All ecstatic. Yet each exhibiting such different reactions to their favourite team winning a game. Such is the nature of being human and of the differences between varying personalities and temperaments. Indeed, simple occasions such as watching a rugby match, often highlight just how unique and different each of us are. As the Psalmist proclaims:

“Oh yes, you shaped me first inside, then out; you formed me in my mother’s womb.

I thank you, High God – you’re breathtaking!

Body and soul, I am marvellously made!” (Psalm 139: 13-14, The Message).

What is personality and temperament?

The “inside” uniqueness the Psalmist is writing about has to do with more than just gifts, abilities and motivations. Personality and temperament features are also very much a part of the puzzle that is “me”.

So what is our personality and temperament? They are somewhat slippery terms and difficult to be precise. How hard they are to define is emphasised by the Oxford Concise Dictionary’s rather unsatisfactory answers – personality being “the combination of characteristics or qualities that form an individual’s distinctive character” while temperament is “a person’s nature with regard to the effect it has on their behaviour”.

Not only do we struggle to identify exactly what these terms describe, we also find it hard to distinguish between them. Are they essentially the same thing, or are they two related but separate elements of our nature? Some say one, some the other.

For our purposes, it doesn’t matter which theoretical position you support. All of us have a unique personality which is a result of both inherited and learned traits. It deeply shapes the way we perceive and respond to situations and other people.

Personality testing

In the popular press, psychology tests abound. Try doing an internet search and see how confused you can get!

There’s nothing new about analysing personalities. Hippocrates put together some ideas on the subject about 2,400 years ago. He was a Greek doctor and philosopher and after years of observing patients, noticed that although none of them were exactly the same, many of them behaved in similar ways in similar situations. He came up with four personality types and gave them names from four fluids in the body which he thought caused them – Melancholic (gloomy and pessimistic due to too much black bile); choleric (bad-tempered and controlling due to too much yellow bile), phlegmatic( calm and balanced because of having too much phlegm), sanguine (passionate and cheerful resulting from too much blood!).

Fortunately the body fluids explanation passed away, but the understanding that people could be “typed” according to preferred responses remained.

How helpful are personality tests?

Over the years, there has been a proliferation of personality/temperament tests developed, some of which still group certain traits into personality types.

While personality researchers differ to some degree on the number of different personality traits we each have, currently there seems to be some consensus on five broad factors – each composed of a number of aspects.[1]Personality traits (simply defined) offer insights into areas like a person’s tendency to be extraverted or not; the degree to which they are willing to accommodate others; their tendency to be structured or more flexible in their approach to organisation; their tendency to stick with what has worked in the past versus an openness to new ways of doing things; and, their emotional responses to demands and pressure.

The strength of any personality questionnaire is the self-understanding that develops from considering one’s preferences. All of the insights gained from this and more complex personality information have potential for helping us understand how we might fit within specific occupations, work settings, and teams.

Personality- Handle with Care

The usefulness of personality related exercises depends on how accurately we see ourselves and our behaviour. It’s easy to fall into the trap of selecting certain preferences that are attractive to us because we don’t usually respond that way – but wish we did! For example, if you score more as an introvert, and tend to be reserved and less exuberant by nature, you may find yourself choosing to identify with high-energy, outgoing traits that are more associated with extraversion. The result, if you’re not careful, is that you fill out a personality indicator according to the type of person you would like to be, rather than the person you really are. For that reason it can be helpful to ask close friends or colleagues for their insights. These may either confirm or balance out your own understanding of your personal style.

Personality questionnaires are valuable only in as much as we use them to understand ourselves and one another rather than using them to create stereotypes.

It’s true that our personalities are relatively stable, but we are also constantly growing and developing. Not many of us fit the nice, clean categories described by the personality type approach. A little knowledge about ourselves can become a dangerous thing.

The same is just as true in how we see others. While we acknowledge our own uniqueness and recognise that we don’t fit precisely into certain patterns, we are sometimes reluctant to extend the same courtesy to others. It’s only too easy to put friends and acquaintances in one personality group or another, and then begin to define their behaviour and responses according to that pattern. There is nothing more destructive, and we all need to beware of this.

On the other hand, when it comes to understanding the people around you, knowledge of personality is helpful. You’ll become aware that the reactions of others and their ways of doing things may be different because of their uniqueness, not because they’re trying to make life difficult for you! This can enable you to “give them space” to be who they are. You can learn how to relate and work with them in ways that are consistent with their own style.

Who is the greatest?

There is no “best” personality or personality type! This understanding is fundamental to the use of personality tests. Whatever personality type you identify yourself with will have some strengths and some limitations. My inclination to be decisive and assertive might be a God-given attribute, but if I do not learn to temper it with a consideration for others, it can become very destructive in any leadership I might undertake. Likewise, my inherently tolerant, considerate and peacemaking nature is a wonderful attribute for working with others, but it can easily lead to avoiding conflict. It may cause me to compromise when the right and loving response may well demand that I speak up and voice concern.

While there is no “best” personality type, in certain cultures (including organisational cultures) one trait may be more valued and socially desirable than another. We need to be aware of this, and be able to accept the traits we have whether or not they are considered desirable by the world around us. God has made us unique, and each personal style is a wonderful expression of God’s creativity.

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI®)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsWhile there are a number of appropriate personality questionnaires or inventories in this area, one widely used among career and human resource professionals is the Myers Brigg Type Indicator®. Because we know of many people who have benefited from using the MBTI and there are many resources readily available using this tool, we offer the following introduction.

Developed by Isabel Briggs Myers and her mother Katharine Cook Briggs, the MBTI® is based on the observations and theories of Carl Jung. There are a number of MBTI questionnaire forms available. They differ in length, according to their purpose.

Those completing the questionnaire are asked to choose between two possible preferences. As a result, they are assigned to one of sixteen different categories or types (these are made up from the letters representing each preference).

The MBTI revolves around four key considerations. They are:

How we are energised – is it primarily by interaction with others and activity (Extraversion) or is it mainly by the inner world of thoughts and reflection (Introversion)?

What we pay most attention to – do we focus on facts, data and reality (Sensing) or do we focus on possibilities and respond to hunches (iNtuition)?

How we make decisions – is it primarily through reasoning, analysing and trying to be objective (Thinking) or is it mainly by way of the more subjective and personal issues of values and feelings (Feeling)?

How we approach organisation – is it primarily through being organised, decisive and systematic (Judging) or is it a more flexible and spontaneous tendency (Perceptive)?

The worship team –“Type” in action

It’s Thursday night and the church worship team has just finished running through the songs for next Sunday’s services. Rose is rostered on as worship leader, a role that she enjoys. It is never a problem for her to find words to fill the gaps between songs, and her enthusiasm tends to lift others. The downside is that some nights she goes away from the practice wishing she hadn’t said quite so much, and sometimes she wishes she could be more like her friend Naomi who is on the keyboard. Naomi is an extremely thoughtful person – she plays the keyboard with such sensitivity. As a matter of fact, Rose would love to have talked to her about how she thought the practice went, except that Naomi was the first to leave. Truth is, Naomi is frequently the first to leave most social events. Rose can never understand this. She herself could go on for hours. In fact, why doesn’t she suggest they all go somewhere for coffee?

Meanwhile Will, Stu, Sarah and Steve are discussing how things are going at church with the music. Steve has just come back from a worship leaders’ workshop that the others couldn’t get to, and he is fizzing with ideas of new possibilities for the group. (In fact, he has some suggestions about a couple of new things they could try on Sunday.) He can see that these new possibilities could improve the way worship is done. Stu is immediately cautious. He thinks that Steve is never satisfied, always wanting to go on to something new and untried. Often these things seem little more than gimmicks, and Stu can’t see the point in changing a formula that already works well. This means that they can clash a bit – especially as Stu is the worship group’s representative on the church leadership team.

Will joins in the conversation. He likes the sound of what Steve is saying … and besides it’s never too late to change the plan. In fact, he thinks that sometimes they plan too much and would be better to go with the flow more in their services. Sarah, on the other hand, glances impatiently at her watch and makes the comment that it’s too late to go altering things. It’s the end of the practice and it’s all been decided on. Changing now will just frustrate her and everyone else.

Linda standing nearby picks up on some of the criticism being expressed, and adds her analysis of the music. She is focused on the task – who is doing what, what they could do different, how it could improve. Some of the others become tense as they listen. Will tries to smooth things over. He hates to see team members in conflict. For him it’s more important to preserve relationships and not hurt people’s feelings. He suggests that they shelve this for a while. Stu agrees, but knows the new conflict will remain an issue until they make time to discuss it further. He schedules a meeting for this purpose.

Extraversion/Introversion

Having a preference for introversion (like Naomi) doesn’t mean that you don’t like people or are not sociable, but rather that you gain much of your energy from your “inner world”. Consequently, those who identify with this grouping find they require less contact with people than those with a preference for extraversion, before they reach a comfortable level of stimulation. Once beyond that, it is easy for them to feel overwhelmed, so they are more protective of how they spend their time and need “time-out” to restore their energy.

People with a tendency for extraversion (like Rose) thrive on contact with people. They are energised by their “outer” world. They enjoy being in the midst of social interaction and having lots to do. They are uncomfortable with long periods of time spent alone.

Many people while identifying with one or other of these preferences (introversion or extraversion), also show behaviours associated with the other at times.

The following summary may help to describe more what these preferences look like:[1]

Extraversion Introversion

Energised by being with people Energised by having time to themselves

Tend to initiate interaction with others Tend to let others initiate interaction

Say what they are thinking as they are thinking it Think through what they want to say first

Have a lot of friends and acquaintances Prefer a smaller group of close friends

Become edgy if spending a lot of time alone Can be drained by a lot of time with others

Are happy to be the centre of attention Tend to avoid being the centre of attention

More likely to speak, less likely to listen Listen well, but reserved about own information

Like action Prefer to think and reflect about things

Are stimulated by interruptions Find interruptions disruptive

Enjoying having lots on their plate rather than little Prefer to have one thing happening at a time

Alistair:

One occasion when I was working with a leadership team, I remember gaining an unexpected and valuable insight from my understanding of personality type. At the time I was constantly feeling misunderstood by a woman on the team, even though she was a close friend. It all fell into place one day when I heard someone explain: “Extraverts talk in order to think, while introverts think in order to talk.”

Suddenly it dawned on me that this woman, who was an introvert, was taking everything I said quite seriously, even when I (an extravert) was just brainstorming ideas off the top of my head. More than that, she was getting upset that I was so indecisive and kept on changing my mind. I had to explain that I was just thinking out loud and needed help to clarify my thoughts. At the same time I began to see that when she spoke she had thought carefully about what she was saying, and needed to be taken more seriously than I had realised.

Sensing/Intuition

The sensing-intuition dichotomy reveals the types of information that we pay most attention to. This can lead to quite big differences in our day-to-day lives. People who have a preference for the sensing function (S) are very aware of sensory information – things they see and hear. They notice detail, and are good at both measuring and documenting what is around them. They are “hands-on” in their approach to things. Based on their experience they have developed an orderly approach to whatever they are doing, and they value the systems they have come up with. Just like Stu they have an appreciation for the accepted ways of doing things. Sometimes they need help to see “the big picture”.

In contrast, people with a preference for intuition (N) like abstract and theoretical information. They prefer to find out if there is a novel way of approaching a task and (like Steven) are not afraid to break with convention. They spend a lot of time thinking about the future and are “big picture” people. As a result they are sometimes vulnerable because of their low tolerance for details.

Sensing OR INtuition

Very practical with good common sense Inspirational, insightful, and innovative

Focus on accuracy Focus on creativity

Tend to think in terms of the present rather than future Prefer to think of the future

Very methodical when presenting information Present data in an innovative way

Base own practice on past experience Base own practice on inspiration

Identify details but may miss the “big picture” Identify the big picture but may miss details

Enjoy “hands-on” activities Enjoy thinking about ideas and possibilities

Prefer applied information Prefer theoretical information

Have a realistic approach Have an idealistic approach

Literal in expressing and receiving communication Figurative in speech, using lots of metaphors

Annette:

I remember how much I loved writing essays in high school English classes, especially when having to identify ideas and themes in literature. This continues today in my preference for dealing with theoretical information, which is an aspect of a preference for intuition.

I have learned to enjoy the strengths of the intuitive style but also recognise some its limitations, and try to compensate for those. For example, some of those close to me with a preference for sensing, help me evaluate the practicality of some of my ideas and dreams without pouring cold water on them. That’s something I greatly appreciate.

Thinking/ Feeling

The thinking (T) and feeling (F) dimension is about what people consider most when it comes to making decisions. Will has a preference for feeling – basing decisions on values, a willingness to provide warmth and nurture, and a focus on relationships. Sometimes this approach makes the person with a preference for feeling seem “easily influenced” because of their reluctance to upset others, and they may tend to try and avoid conflict – even when it may be quite constructive.

The person with a thinking preference, like Linda, values fairness over harmony. Thinkers can be outspoken and can be seen as coolly analytical rather than accepting by others. They are logical and objective in their approach to decision-making – a style which can be infuriating to their feeling friends, who tend to be more subjective in their approach. While thinking seems to best fit a male stereotype and feeling the female stereotype, it is not gender based. However this misapprehension may explain why men who prefer to base decisions on more subjective means, and women who are more logical and fair in their approach, feel as if they are moving against the current of people’s expectation.

Both the thinking and feeling approaches have positive contributions to make to the decision making process.

Thinking OR Feeling

The “flaw-finders” of life; can be quite critical Tend to be the “people-pleasers” of life

May seem insensitive and uncaring at times May seem easily influenced by others

Take an analytical approach to life Are sympathetic in their approach to life.

Justice and fairness are strong values Empathy and harmony are strong values.

Consider truth more important than tact Considers tact important

Enjoy developing ideas for data, structures, and things Enjoys developing ideas for people

Will give praise for results rather than effort Praises effort as well as results

Impartial; their head rules their heart Subjective; heart rules the head

Doesn’t shy from conflict; may invite it Takes conflict personally; tries to avoid it

Tend to be task-focused in a group Tend to be people-focused in groups

Annette:

I have a preference for feeling – but have become quite comfortable with a thinking approach. When I am with strong “feeling” people I find myself taking a more “thinking” approach as if to balance this, and yet when I am with strong “thinking” people I am reminded that that is not my natural preference – though I do appreciate what a thinking approach offers. As I have got older, and especially with my studies, I have developed my “thinking” side more. However many of my ideas are about helping people to grow and learn – and that, I think, is the clue to my original preference.

Judging/Perceiving

The dimension of judging (J) and perceiving (P) focuses on how people approach organisation and planning. Those with a judging preference are very structured people who thrive on pre-planning and organisation (like Stu), and prefer when things are decided (like Sarah). They enjoy the satisfaction of completing a project, and follow through on their commitments well. Sometimes they can be so structured that they miss opportunities that come “out of the blue”.

People with a preference for perceiving enjoy the challenge of beginning a new project, but can lose interest quickly. The result can be a number of unfinished tasks. They enjoy leaving their options open in order to respond to late-breaking information (a tendency seen in Will). They are flexible, but are sometimes seen as unpredictable.

Judging OR Perceiving

Tend to plan ahead Prefer not to plan too much in advance

Use a “to-do” list and a diary and/or timetable If they use lists, they seldom tick off items

Are anxious until a decision is made, then they relax Anxious after decisions in case other options arise

Prefer to work at something before they play Try to make their work like play, or combine both

Feel great satisfaction when completing a task Experience satisfaction as a project commences

Keep to deadlines Deadlines are seen as negotiable

Prefer to make steady, regular inputs into projects End up doing a lot of work at the last minute

Like to have a tidy and organised work area Can tolerate less tidiness and obvious organisation

Can seem inflexible to suggested change Enjoy spur-of-the-moment, spontaneous events

Structured in their ways of doing things Are flexible in their approach to doing things

Alistair:

At one stage I was involved in the leadership of a rapidly expanding organisation. It presented me with a big challenge, and I had to learn some new ways of operating. In particular I found myself needing to have a much better organised diary and timetable, and to put more time into training others to perform delegated tasks. The whole assignment was something which I found quite stressful.

When during this period I did the MBTI for a second time, I discovered that my answers suggested that my natural P had turned into a J. On reflection, I realised that the mode I was having to operate in at that time was influencing my answers. What I learned was that although I can operate in a much more organised mode for significant periods of time, if this is unrelieved I get stressed. As a result, if work demands a lot of organisation and administration from me, I also need time to play in a much more spontaneous way to compensate. It’s good for us to learn to grow in ways we are not accustomed to, but not if we completely lose sight of how we have been put together. We can maintain balance by ensuring that different parts of our lives perform different functions.

Finding Your “Type”

While the people in the worship team story illustrate clear versions of the preferences, many of us may find that we present a more mixed picture of either – possibly changing according to different situations we are involved in.

However, most people are able to identify an approach they feel most comfortable with in each of the four dimensions.[2] The combination of their preferences establishes their “type” (identified by each of the four letters of their preferences). For example, a person who prefers Extraversion, iNtuitive, Thinking and Judgement would be an ENTJ type.

The MBTI identifies sixteen possible combinations. The way the MBTI and other related resources develop these types, gives individuals some useful and quite specific information. While it is not our intention to attempt to unpack the types here, we recommend that you pursue some of the resources noted.

Many personality “type” questionnaires can be helpful. Nevertheless they make us quickly aware that none of us fits the mould one hundred percent. We are just too unique for that. The insights we can gain have the potential to help, but is also useful to remember the cautions we have outlined earlier in the chapter.

Personality and career fit

While it’s impossible to define exactly which careers fit particular types, understanding your preferences can be helpful in identifying job types, environments, and even team situations that are most likely to align with your strengths and preferences.

For more help see Allen L. Hammer Introduction to Type and Careers CPP or Paul D. Tieger and Barbara Barron-Tieger, Do What You Are (Scribe Books, 2001). These offer help on interpreting your “type” for career-related issues.

Personality and Spirituality

What kinds of approach to spiritual development do different types find most beneficial? A lot of work has been done in this area, exploring the relationship between personality type and the ways we pray and express our spirituality. To investigate further we suggest you look at Soul Types by Sandra Krebs Hirsh and Jane A.G. Kise.

A helping-hand

We’ve already mentioned that there is a lot of personality information available in books and the internet. Personality puzzles, tests and questionnaires that are so readily available tend to be less dependable in the information they offer. Even standardised tests differ in their ability to actually measure what they say they measure, and in the likelihood that the result you get today will be repeated on another occasion. If you are really serious about understanding how personality contributes to your SoulPurpose we recommend you seek professional advice.

When it comes to career and vocational issues a good place to start would be a career consultant or human resources professional who is qualified to administer and interpret personality questionnaires. In this way you are more likely to receive a balanced interpretation of how your personality may influence your preferences and options.

A Final Word

Last, but definitely not least - don’t allow the results of any personality questionnaire to dictate your future. It is not the whole truth about you. Use them as one source of information about who you are – not as the only source. Personality is just one aspect of our uniqueness and needs to be kept in perspective with the other aspects we have identified in this workbook section.

Exercises and Resources for Exploring Personality

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsA structure for using this chapter personally

If you have access to some personality information about yourself like the MBTI, think about how your preferences may have influenced your past activities and work. Have another look at the information you came up with in the Autobiography exercise and look for evidence of aspects of your personality at work.

Feedback from friends: growth in maturity

If you’re studying this material with others, you may like to get their feedback on the following possibilities.

1. How might my personal style affect:

The type of work I might be best suited for?

The kind of working relationships I might prefer?

2. Consider your present work or role. How does it allow you to make the most of your personality type? What opportunities does it offer for you to grow further, and to make a greater contribution?

3. Can you identify a particular limitation of your personal style that you could work on?

Resources

The MBTI® is well worth doing through a qualified test user. See the contact address below for more information.

The Keirsey Temperament Sorter is available online. It sorts people into one of four main temperaments – Guardians, Idealists, Artisans and Rational – as well as sixteen personality types.

Websites

http://www.personalitytype.com

Contact

For more information regarding the use of the MBTI® contact your local MBTI service provider. (For example, in New Zealand, NZAPT, PO Box b9842 Wellington.) The MBTI® is a registered trademark of Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc.

Books

David Keirsey and Marilyn Bates, Please Understand Me (Prometheus Nemesis Books, 1984)

Sandra Hirsh and Jean Kummerow, Life Types (Warner Books, 1989)

Jane Kise, David Stark and Sandra Krebs Hirsh, Lifekeys (Bethany House Publishers, 1996).

Otto Kroeger and Janet M. Thuesen, Type Talk (Tilden Press, 1988)

Allen L. Hammer, Introduction to Type and Careers (Consulting Pyschologists Press)

Paul D. Tieger and Barbara Barron-Tieger, Do What You Are (Scribe Books, 2001).

Sandra Krebs Hirsh and Jane A.G. Kise, Soul Types (Hyperion, 1998).

Sandra Krebs Hirsh and Jane A. G. Kise, Work it Out: Clues for solving people problems at work (Davies-Black Publishing, 1996).

Renee Baron, What type am I? Discover who you really are (Penguin, 1998).

Chapter 5: What's in My Toolbox? Talents, Skills, and Interests

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsTo do easily what is difficult for others is the mark of talent. (Henri Frederic Amiel)

Wayne’s misery

There are always things to repair around home. A tap leaks, a door jams, a leg falls off a chair, the motor mower breaks down…

Both my father and father-in-law are handymen and can fix most things around the house. So I grew up assuming that all men just naturally became expert at those household fix-it and build-it tasks. It was, I assumed, simply a matter of applying myself to the job at hand.

But somehow it wasn’t like that. Not for me! Those day-to-day handyman jobs that are part of family life – it took me a while to realise how good I had become at avoiding them. Eventually guilt would get the better of me and finally I would attempt them – often weeks or months later. They always seemed to take ages, and I invariably found them so difficult that they left me in a bad mood.

Sometimes I would visit a friend and notice a newly built fence or a well restored cabinet. I’d ask him how he managed it. Or I would request some advice on how to repair leaking windows. The answer would often frustrate me intensely – “Oh, that’s easy. All you have to do is…” Well it may have been easy for them, but my attempts to do similar feats were nothing short of pathetic.

Eventually I figured it out. I was technically inept. The few skills I did have in the fix-it and build-it arena have been developed through dogged perseverance, certainly not through any natural aptitude. Fixing the rattle in back of the car may be “easy” for some of my friends, but it’s just plain hard work for me. Of course, everything is easy if you have the know-how or skills or abilities. But when you don’t … they’re all dauntingly difficult.

It’s only natural then that as Arthur Miller notes: “your agenda will be driven by your design. Furthermore, not only will you focus on what you value most, you’ll avoid things that hold little motivational value for you, or the things you don’t do well.”[1]

That’s me. Now I know why I felt so frustrated. The fact that I kept avoiding fix-it jobs should have told me what I wasn’t gifted or skilled in.

Considering our toolboxes

A key element in each of our fingerprints is the unique mix of talents, skills and gifts that we possess. They’re like a toolbox that we carry with us through life. Some of the tools are ones we seem to have possessed right from the beginning. As we progress through life, those innate skills often get sharper and more versatile. But something else happens too. Along the way other, new tools get added to our box.

The Autobiographical exercise in chapter 3 will have set you thinking about your own toolbox of talents, skills and interests. You will have used a varied mix of capabilities to do whatever tasks you listed there. Now we invite you to create a more extensive inventory. One way to do this would be for you to take a blank page and begin listing what you know to be your abilities. However, starting cold like that is difficult, so we suggest here some exercises that might help you.

But first let’s look at what we mean by the various items in your toolbox. The differences between abilities, talents, gifts, skills, competencies, and aptitudes are quite subtle. These words are often used as synonyms and there is a blurring when it comes to making absolute distinctions between them.

For our purposes we do want to suggest some differences, while still recognising that there is overlap. So the arbitrary distinctions we are about to adopt are only for the sake of convenience and clarity. Remember that, in general use, these words are often not sharply defined.

Here, then, is how we will use three terms:

Talents – those natural, God-given abilities we have been born with. To be fully used, talents need to be developed and grown, but their existence is already built into our fingerprint.

Skills – the know-how and competencies we have gained through the course of our lives, as a result of both formal training experiences and informal learning. Skills are not necessarily intrinsic to our make-up, though the ones we most quickly gain and most effectively use are often closely associated with our natural talents.

Interests – those activities and subjects that grab our attention and excite us. They are the things we become absorbed in and enthusiastic about, and which engage our passion.

Note: in the next chapter we’ll consider more particularly Spirit gifts. For the moment note that the distinction between talents and gifts is very hazy. If we accept that all abilities/talents/gifts are given by God, then there is no sharp line between “natural” giftings and “spiritual” gifts. (More about this in Chapter 6.)

Interests and talents – Holland's Hexagon

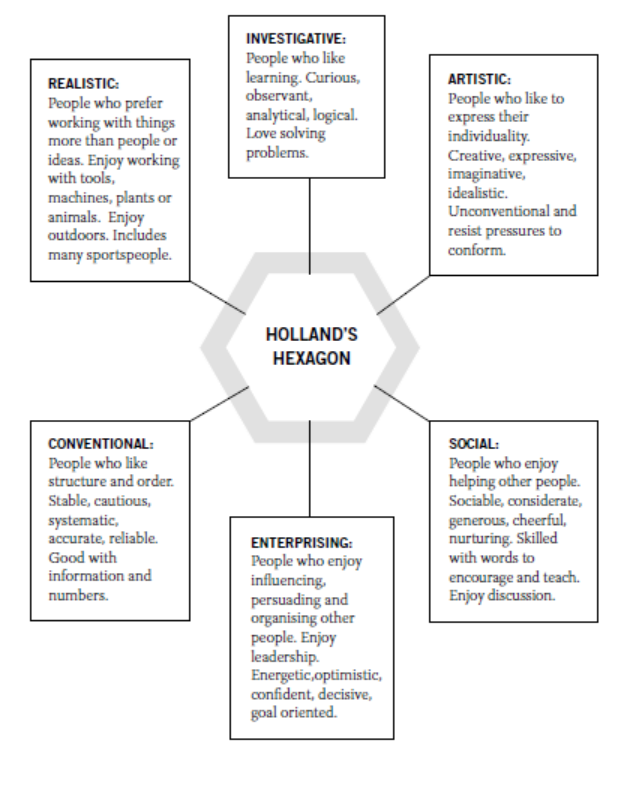

One way of exploring the talents that you have been given is through the work of John Holland and his description of six different preferences. Holland’s work is familiar to career counsellors and has been influential for many years (see the end of this chapter).

Holland suggests that people who have similar interests also tend to enjoy similar work, similar co-workers and similar working environments. Expanding on this Holland describes six different clusters of interests, portraying them in a hexagon. People with interests adjacent to each other on the hexagon have more in common than those further removed or opposite each other.

Note: Holland’s hexagon looks like this:

This diagram has been used in a variety of ways. Richard Bolles invites his readers to imagine it as a party setting and asks them to choose which groups they would enjoy spending the most time with.

Another way of viewing it is as a church congregation where people are asked to divide up into groups according to their interests and hobbies. Alternatively, it can be viewed as people gathered in the different sections of the local library, where they are chatting about the types of books they’ve been browsing.

All these approaches invite you to choose the group you would feel most relaxed with and enjoy spending most time with. Which one is it?

Then imagine this group has left. Which of the remaining groups would you be most attracted to? This is your second preference.

Finally, imagine the second group has also left. Repeat the process to choose your third preference.

NOTE: In considering these categories try not to base it on who you think you should be, or who you wish you were, but look for the best description of who you really are. Often we have developed Christian or cultural biases towards certain interests and away from others. However, it’s important not to let these influence you.

Usually our natural talents and interests are evident from very early on in life. Often other people close to you may see them even more clearly than you do. So also invite feedback from family and friends to confirm the categories you choose. (To learn a lot more about the areas that may fit you best the Strong Interest Inventory™ is also a very useful tool. )

Holland has also developed an elaborate classification of occupations built around these six groups, also taking into account people’s second and third preferences. His work is based on the belief that people will be most satisfied in work environments related to their interests.

It’s also critical to differentiate between those people and activities we’re attracted to and those that not only interest us but also motivate us to action. For example, many people say they love music, but only some are drawn into seriously making music and loving the practice as well as the performance.

Our interests (in the sense Holland uses them) are about us doing naturally what others struggle to do. It’s as though we just can’t help ourselves from doing it because it is so much a part of who we are.

The Realistic tend to be honest, straightforward, practical workers. In interactions with others they don’t like drawn out negotiations, but prefer to get to the point quickly. They want to know what needs to be done and to be left alone to get on with the job and do it right the first time. |

The Investigative tend to be logical, precise, reserved and independent. They prefer to work alone and assemble a lot of information before reaching conclusions. They want to know the reasons behind decisions and prefer information to be presented in a logical manner. |

The Artistic are expressive, imaginative, independent, idealistic, open, unconventional and tolerant. They prefer a creative approach to problem solving and planning, relying heavily on intuition and imagination. They enjoy being given a free reign to discover possible solutions to problems. |

The Social are helpful, friendly, co-operative, understanding and kind. They prefer to network in order to gather information before creating a plan of action. They are good networkers and like a team approach to creating solutions. |

The Conventional are practical, careful, efficient, orderly, conscientious, persistent, reserved and structured. They are happy to accept instructions and prefer to have a clear and structured plan and to follow it. They pay attention to detail and take pleasure in putting the pieces of the plan together. |

The Enterprising are adventurous, energetic, optimistic, extroverted, sociable, self-confident and ambitious. They prefer to lead a team to achieve a goal. They like to focus on the big picture while delegating work by getting others to commit to pieces of the plan. |

A lot more suggestions, based on Holland’s work, about specific careers which may suit specific interest groups can be found in Richard Bolles’ books, What Color is Your Parachute? and The Three Boxes of Life.

Important qualifications

Like the Myers-Briggs personality types we outlined in the last chapter, these categories of Holland’s need to be used carefully. Some people will find them more helpful than others. Be careful not to “box in” either yourself or others.

A second important qualification is to note that while Holland uses his categories in a relatively narrow way – i.e. to help people identify occupations or employment – we suggest that, like all the exercises in this book, they can be helpful for clarifying the bigger picture; that is, all of the roles and tasks we play during our week. So feel free to apply this activity to yourself as widely as you can.

Clarifying Questions

Of course there are many other ways to explore what interests you most like. For example, consider the following questions:

(No need to spend long on these. Just note what answers first come to mind for you and then see if any recurring themes emerge. Don’t get stuck where nothing comes quickly to mind.)

What topics of conversation are guaranteed to keep you talking?

What do you love to do? (hobbies, activities, etc.)

What books do you browse through in bookstores or your local library?

What courses of study have you enjoyed most?

What issues do you feel most strongly about?

What issues would your friends say you feel most strongly about?

If you won or inherited a fortune, which causes/issues would you give money to?

If you were a reporter, what kind of stories would you like to write?

What are your favourite objects?

If you knew you couldn’t fail what would you most like to do?

What sorts of information do you find most fascinating?

Who do you greatly admire?

When you were ten years old, what did you dream of one day becoming?

Skills

As we have already mentioned, skills are related, but somewhat different to talents. We define them as: the know-how and abilities we have gained through the course of our lives, as a result of both formal training experiences and informal learning. Skills are not necessarily intrinsic to our make-up, though the ones we gain most quickly and use most effectively are often closely associated with our natural talents.

As Richard Bolles (author of the bestseller What Color is Your Parachute?) notes, some important things about our skills are:

Everyone has skills.

Most people have far more skills than they have ever realised.

We acquired most of our skills at an early age through informal life experience, rather than through formal training programmes or classroom teaching.

Many skills developed and used in one setting, can also be very usefully employed in other settings, although we may not previously have seen how readily transferable they are.

Many of our skills are not only transferable but also marketable, if we begin to view them from a creative point of view.

Many people have skills that they severely underestimate the significance of, or that they are not aware they possess.

Sometimes we need the assistance of others to help us appreciate and understand the skills that we have acquired.

Bolles follows the Dictionary of Occupational Titles,[2] in which skills are broken down into three major groups – skills applying to Data (Information), to People, or to Things.

The skills are then arranged under each heading in a hierarchy – from less complex at the top to most complex at the bottom.

Skills with People |

Skills with Information or Data |

Skills with Things |

Taking Instructions Serving Sensing / Feeling Communicating Persuading Performing / Amusing Managing / Supervising Negotiating / Deciding Founding / Leading Treating Advising / Consulting Counselling Training |

Observing Comparing Copying / Storing and Retrieving Computing Researching Analysing Organising Evaluating Visualising Improving / adapting Creating / Synthesizing Designing Planning / Developing Expediting Achieving |

Handling (objects) Being Athletic Working with the Earth or Nature Feeding / Emptying Minding Using (tools) Operating (equipment) Operating (vehicles) Precision Working Setting Up Repairing |

EXERCISE

Look at the three lists and note the following:

(a) What do you most enjoy working with: people, data or things? (Some people might like to include animals. If that’s you, feel free to add them as a fourth category, along with some appropriate skills.)

(b) What levels of skills have you developed? Identify your skills at the highest level you have realistically accomplished, because this is likely to include attainment at the less complex level.

(c) Ask a couple of people who know you well to sit down with you and talk about which skills they see you demonstrating most competently. Which ones do they see in you that are valued most by others? Which ones do they detect you enjoy most?

(d) Now look at the more comprehensive list of skills listed below and consider:

Which words describe skills that you believe you have already developed?

1. TICK the skills that you have already developed.

2. UNDERLINE any skills that you think you would like to develop more in the future.

3. CIRCLE your top ten skills (those you think you have developed best).

Note: skills may be marked in more than one category. Also these are in no way exhaustive lists, so feel free to add your own additions as you think of them.

Using Analysis, Logic, or Research SkillsResearching Analysing Comparing Organising Categorising Problem-solving Prioritising Systematising Testing Diagnosing Reviewing Evaluating Compiling Designing Surveys Keeping Records Statistics Classifying Other_____________ |

Using Communication SkillsWriting Creative Speeches Journalism Minutes Reports Technical Other_______ Reading Translating Speaking Editing Copying Proofreading Instructing Listening Reflecting Mediating Negotiating Presenting (with audio-visuals) Discerning Other__________ |

Using Leadership SkillsOrganising Leading Making decisions Taking risks Performing before a group Selling Promoting Initiating Other__________ |

Using People Helping SkillsHelping someone in need Listening sensitively Drawing people out Offering support Being an advocate Healing/Caring Counselling/Guiding Motivating Coaching Other_______ |

Using Physical and Manual SkillsAssembling Building Repairing Installing Drafting Precision working Machining Constructing Operating tools or machinery Operating equipment or vehicles Muscular co-ordination Athletic activity Outdoor pursuits Typing Data Processing Gardening Other_________ |

Using Artistic SkillsDesigning Composing Sculpting Displaying Colour consulting Acting Singing Dancing Illustrating Painting Cooking Playing an instrument Conducting Visualising Drawing Other__________ |

Using Management/Administration SkillsCo-ordinating Problem identification Goal setting Policy development Organising Reporting Scheduling Delegating Controlling Budgeting Monitoring Supervising Communicating Forecasting Teaching/Training Other________ |

Using Financial and Number SkillsComputing Programming Data Processing Budgeting Financial Planning Investing Tax preparation Statistics Record keeping Stock-taking Designing surveys Quantifying Calculating Auditing Other____________ |

Using Originality and CreativityImagining Inventing Creating Designing Improvising Experimenting Adapting/Improving Visualising Developing Other___________ |

Using Sensory SkillsObserving closely Examining Diagnosing Touch Hearing Taste/Smell Other_____________ |

Take another look through the lists of interests and talents and skills that you have come up with, and then compile your results in the following tables.

Interests

My primary interests include:

Now circle the two that are of greatest interest to you.

Talents and Skills

List below your most well-developed skills and talents:

List the skills that you are keen to develop and want to use more:

How do your existing interests and skills correspond with the talents and skills that you enjoy using most and want to continue developing in the future?

Feedback from friends: personal reflections in a small group

Do the personal analysis (above) as preparation for your group session. Then in the group take turns to describe your toolbox of talents, skills and interests. After each member’s presentation give the group opportunity to:

Affirm or otherwise comment on your findings.

Mention ways or situations in which they have seen you using your abilities.

Suggest possible further developments you might consider for yourself.

Resources

Richard N. Bolles, What Color is Your Parachute? (Ten Speed Press, 2004)

Richard N. Bolles, The Three Boxes of Life and How To Get Out of Them (Ten Speed Press, 2003)

John L. Holland, Self-Directed Search (Psychological Assessment Resources - package edition, 1994)

Gary Gottfredson and John L. Holland, Dictionary of Holland Occupational Codes (Psychological Assessment Resources – 3rd edition, 1996)

John L. Holland, Making Vocational Choices: a theory of vocational personalities and work environments (Psychological Assessment Resources – 3rd edition, 1997)

Chapter 6: Unwrapping Our Spiritual Gifts

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsGod’s various gifts are handed out everywhere; but they all originate in God’s Spirit…Each person is given something to do that shows who God is: Everyone gets in on it, everyone benefits. All kinds of things are handed out by the Spirit, and to all kinds of people! The variety is wonderful. (St. Paul 1 Corinthians 12, The Message)

Imagine the following conversation:

Barry “Have you found your spiritual gift yet, Jane?”

Jane “I didn’t know I was looking for it?”

Barry “Ha, ha! Very funny! What I meant was, have you worked out what particular gift the Holy Spirit has given you?”

Jane “Don’t know. Maybe it’s the gift of humour?”

Barry “Sorry. That one’s not in any of the lists. It’s not a spiritual gift.”

Jane “What do you mean by spiritual?”

Barry “Well, in the New Testament Paul lists a number of gifts which he says are spiritual – specifically given to believers. Things like prophecy, speaking in tongues, pastoring, evangelism and faith. There’s 19 of them altogether.”

Jane “Why 19? Surely if they’re spiritual, there should be 7, or 77 – or maybe even 777?”

Barry “I don’t know. Anyway, you’re bound to have one of them. All of us are given one by the Holy Spirit when we become Christians.”

Jane “You mean you only get one? That’s a bit raw.”

Barry “Maybe, but at least everyone gets included. After all, we’re all part of the body. Even someone with the gift of helps feels like they have something to contribute.”

Jane “So what’s your gift, Barry?”

Barry “Just quietly, and in all humility, Jane, it’s – ah – prophecy.”

Jane “Oooh! Bit spooky, eh?”

Barry “I take it very seriously, Jane. Being a mouthpiece of the Lord and all that. Anyway, do you have any idea what yours might be?”

Jane “Maybe it’s teaching?”

Barry “How do you figure that?”

Jane “Well, it’s what I do during the week, isn’t it. I was born to teach. I just love getting alongside those six-and-seven-year-olds in my class.”

Barry “No-ooo – you don’t get it. Just because you have a natural talent for teaching, doesn’t mean to say you have a spiritual gift of teaching. There’s simply no link between the two. Anyway, you didn’t become a Christian until you were 25, did you? By that time you were already teaching. So the Holy Spirit can’t have given you it.”

Jane “Doesn’t make much sense to me.”

Barry “Well, it is a bit mysterious. But hey – who are we to argue? Anyway, it’s critical you find out what your gift is.”

Jane “Why’s that, Barry?”

Barry “Otherwise you’ll find it hard to mature as a Christian, Jane. And besides, if you don’t know, it’ll really limit your effectiveness.”

Jane “So what do you suggest, Barry?”

Barry “I was hoping you’d ask that. Mind you, it took you a while! No, just joking. But I do have the very thing for you. It’s an eighteen-week course called, How to Find your Spiritual Gift. I think you’ll find it most helpful, Jane. What do you think?”

Jane “Maybe. But I still want to know why humour isn’t on the lists.”

A fog of misinformation