Vocation in Historical-Theological Perspective

This in-depth article is a companion to the "Vocation Overview” article by the Theology of Work Project. In it, Theology of Work Project steering committee member Gordon Preece presents an historical-theological perspective on vocation at greater length than is possible in the TOW Project's main articles. This resource represents the views of the author, individually.

Introduction – Vocation in Contemporary Society

Vocation (or calling) language is still common in both religious and secular sources as this spectrum of examples shows:

- Baylor University advertises through the mouth of a new college student: “I got calls from UNC Emory and George Washington. But I found my call at Baylor.” This raises the question “What does God call us to and how?”

- In another ad MDiv student Michelle Sanchez says “I wanted to become a CEO, but then God called me to something greater….I sensed God was calling me to full-time ministry.” This raises the question “What is the value of ‘secular’ work and is paid church ministry greater or more sacred?”

- An article entitled “The Case for Kids” asks are women who have children merely “breeders”? Or is having children the call of all women able to do so?[1]

- The back-cover blurb of Max Lucado’s book He Chose the Nails[2] says “Max Lucado has a blessed calling: Denalyn calls him Honey. Jenna, Andrea, and Sara call him Dad. The members of the Oak Hills Church of Christ in San Antonia call him their preacher. And God calls him His.” This raises questions of our calling to spouse and family, God’s people in ministry, and God himself – all through the ways we are addressed, named or called by our most significant others.

- The caption in a recent ad for a mobile phone with vibrator read “I can feel when somebody is calling me. It’s not supernatural, it’s technological.”[3] How do we experience God’s call in a cacophonous, technological world of thousands of calls?

This collection of “calling” quotes raises the question where do our concepts of calling come from and what does Scripture say about calling? This paper will start with the apostle Paul (and his great interpreter Luther) who is central to the debate about calling and closest to our post-resurrection situation, move to the gospels, then examine broader biblical, especially Old Testament themes of creation and providence. We will then seek to synthesize and balance the scriptural material through connecting calling to the doctrine of the Trinity as a summary of the story of salvation or God’s work, as a model for human work. We will finally apply this scriptural and doctrinal material to the question of vocational guidance – does God call us to particular work and if so how?

Call in Paul and Luther

A helpful contemporary definition of calling is “the truth that God calls us to himself so decisively that everything we are…do …and have is invested with a special devotion, dynamism, and direction lived out as a response to his summons and service.”[4] But what does calling or vocation ("to call” in Latin) mean in Scripture?

The general New Testament view stresses a Christians' common calling to conversion and corresponding Christ-like character or holiness (cf. Romans. 1:7; 1 Corinthians 1:2, 9, 1 Cor. 1:9, 26, 2 Cor. 3:18; Ephesians 4:1; 2 Timothy 1:9; 1 Peter 1:15-16, 2:9, 1 John 3:2-3). Our common use of the concept of calling to a particular social or work role dates back to the early 16th century when Protestant Reformer Martin Luther interpreted "calling" this way in 1 Cor. 7:20, opening it up to all Christians in the light of his doctrine of the priesthood of all believers. This replaced the millennium-long traditional Catholic sense that a calling only applied to the priesthood or monastery. The monastic tradition exalted the “perfect” contemplative, Mary-like life of poverty, chastity and obedience (to the church) over the “permitted’ active,[5] Martha-like life (Luke 10:38-42) of secular work, marriage and obedience to the State, thus making an eternal principle out of a particular incident.[6]

But many today say Luther’s view of an individual calling to a social or work role is due to his incorrectly translating the Greek term klesei in 1 Cor. 7:20 as “vocation” or “calling,” in the sense of occupation. This influenced the King James Version’s (KJV) literal English translation "Let every man abide in the calling wherein he was called." Contrast the more liberal modern translation "Let each of you remain in the condition in which you were called” (NRSV) or converted.

To decide between these two views Paul's condensed summary statement in 1 Cor. 7:20 (cf. 1 Cor. 7:17 and 7:24) needs its context unpacked. The Greek (soul versus body) dualism of the Corinthians and their desire for upward social and spiritual mobility caused them to question Paul about marriage, seeking to change to an apparently more spiritual, heavenly, unmarried status (1 Cor. 7:1, 25 cf. Matthew 19:12 and Luke 10: 38-41). In response, Paul states his general principle of staying in the same social status/class and roles as when they were converted. After all, Christ called or converted them there, making their social roles relative, not absolute.[7]

These "intertwined" senses of "calling" cause Paul to nearly jump, like Luther, to seeing "the setting in which one is called as 'calling' itself." But "at most 'calling' refers to the circumstances in which the calling took place."[8]The prepositions are key here. The difference is between calling in a situation when converted (Barrett and Volf) and calling to a situation (Luther).[9]Os Guinness captures the sense of our primary call: “First and foremost we are called to Someone (God), not something (such as motherhood, politics or teaching) or somewhere (such as the inner-city or Mongolia).”[10]

Yet, while God's call to Christian conversion and conduct is not equated with these social spheres, it is closely related to them and sanctifies them in 1 Cor. 7:17ff. A secondary use of calling language for relational and work roles is still justified, as Fee notes:

Paul means that by calling a person within a given situation, that situation itself is taken up in the call and thus sanctified to him or her. Similarly, by saving a person in that setting, Christ thereby "assigned" it to him/her as his/her place of living out life in Christ .... Precisely because our lives are determined by God's call, not by our situation, we need to learn to continue there as those who are "before God" .... There let one serve the Lord, ... whether it be a mixed marriage, singleness, blue-or white-collar work, or socio-economic condition.[11]

Paul then illustrates his basic principle of “staying” put in one’s social situation and occupation through the ultimate unimportance of both circumcision (vv. 18, 19) and slavery/occupation (vv. 21-24 cf. Gal. 3:28) compared with salvation. Yet instead of the Corinthians’ view of our relational/occupational setting as mere stage scenery or scaffolding to be discarded as soon as possible, Paul sees it as potentially part of our primary calling to live out salvation but in our secondary social and work roles. Like sacraments, callings are an outward, visible sign of inward, spiritual transformation.

For Paul, our relational and occupational settings are not accidental but providential. Staying in the situation you were in when called or converted potentially converts even the most unpromising situation into a place of service to God. But this is not a rigid law. Paul sees occupational or role change as undesirable in some cases e.g. selling oneself into slavery or changing racial identity (uncircumcision); and unnecessary but possible or desirable in others, if e.g., a slave-master or non-Christian spouse allows one’s freedom (v. 15, 21).

The Corinthians therefore need not abandon their social roles, nor must they stay in them. Paul's explanation in v. 29-31 stresses the tension of Christian freedom in marriage and work in a fallen world, between the now and the not yet dimension of our call to God’s Kingdom: “the time is short. From now on those who have wives should live as if they had none; … those who buy something, as if it were not theirs to keep; those who use the things of the world, as if not engrossed in them. For this world in its present form is passing away.” We are called to stay in our worldly situations/roles or creation but our fundamental allegiance and concern is called away towards the new creation.[12]

In understandable reaction to a millennium of monastic denial of created roles like marriage and work in their super-spiritual enthusiasm for the away part of the tension, and from his own Medieval conservatism, Luther stresses the stay (or creational) side. In equally understandable reaction to the later “Protestant Distortion”[13]or Protestant Work Ethic’s idolatrous elevation and secularization of work into our primary calling, even a “work” earning salvation, contrary to Luther,[14]Volf stresses the away (or new creational) side. The Spirit of the new creation transforms our social and work situations to allow gifts to flourish. [15]

In sum, Paul challenges the Corinthians and us to maintain our availability to God’s kingdom or new creation but without abandoning the created roles it will preserve and perfect.While there is a tension between our roles in creation and in God's Kingdom (1 Cor 7:29-31), between being called to stay and being called away, the two are ultimately reconciled, for the Kingdom is "creation healed" (Hans Küng).[16]

Call in the Gospels

When we turn to the Gospels with this interpretive grid we see that contrary to the dominance of the monastic “Catholic Distortion” and a Protestant form of the same distortion in terms of so-called “full-time Christian ministry,” Jesus’ followers were not all called away from their occupations. Jesus' followers came from all walks of life and many stayed in them. The first group, the disciples, included middle class fishermen with their own boats and servants. Fishing was one of the biggest businesses in Galilee - fish being the basic source of protein.[17]Levi was a wealthy tax collector (Luke 5:29). To answer Jesus’ call and follow Jesus they left behind relative wealth and security (Matthew 4:18-22; Mark 1:14-20) as the rich young ruler failed to (Mt. 19:16-30).

The second group, the stay-at-home supporters, followed Jesus closely and continuously, although they did not travel with him. They supported him and his disciples from their relatively well off positions.[18]These include Peter's mother-in-law (Mark 1:29-34), Lazarus (John 11) and his sisters Mary and Martha (Luke 10:38-42), wealthy men like Joseph of Arimathea (Luke 24:50-51), and the wealthy women "who provided for them [Jesus and his disciples] out of their resources" (Luke 8:3). This group included followers of Jesus who stayed in their occupations.

A third group, the crowds, included a wide range of people, less intimately and regularly connected to Jesus. Many were called to stay in their situation and testify to their salvation like the Gadarene demoniac after his healing (Mk.5:18-20;cf. 8: 26; Matt. 8:13; 9:6). Tax collectors like Zacchaeus (Luke 19) were called away from greed but not from their occupations. Compare Luke 3:10-14 on repentance on the job, not from the job, for the ethically challenged occupations of soldiers and tax collectors.

In sum, Jesus called his followers to lives of redemptive sacrifice and celebrative delight. Perhaps the outer ring of followers, including especially Zacchaeus, is the best 'type' for professional people ... These 'righteous rich' committed their possessions and their positions in the world to the work of redemption in the fullest sense ... A poverty of spirit animated their delight, and this proved itself in free and effective actions of good will toward the poor and the powerless.[19]

A Broader Biblical, Creational and Providential Basis of Vocation

Luther’s great rediscovery of “the priesthood of all believers” saw our primary calling to Christ consecrating our secondary but significant social roles to Christian service. However, Luther’s perhaps over-enthusiastic stress on calling to specific occupational roles, his static medieval stress on staying permanently within them, and later Protestant secularizing and individualizing of calling have led many to throw out the baby with the bathwater on the grounds that he misread 1 Cor 7.

However, we, like Luther, can draw a biblical theology of work deductively from broad biblical themes.[20]For example, our first and foundational calling in Scripture is to image and reflect God’s royal reign through the creation mandate, to “have dominion...,be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it” (Genesis 1:26-28 NRSV). As God’s people we are called to anticipate and reflect the Kingdom of God in our domestic partnership with each other as male and female and in caring, cooperative dominion over creation. This involves reproductive and productive work for both men and women in their distinctive ways.

We image God through our work because the biblical God is the first worker. God is the one who effortlessly says “Let it be.” Everything visible and invisible is “the work of his hands”. He is the master craftsperson - the potter (Isaiah 45:9, 64:8), the architect of the universe (Proverbs 8:22-31), the homemaker (Luke 15:8-10), the weaver who knits humans together in their mother’s womb (Psalms 139:13-16).[21]

Recently, some theologians, most notably Pope John Paul II, have depicted humans as “co-creators” with God.[22] This is true in the sense that our work (and rest) should be modelled on God’s creative work (and rest), "six days you shall labour and do all your work ... for in six days the Lord made the heavens and the earth, the sea and all that is in them . . ." (Exodus 20:9-11). However, our work is secondary and creaturely and does not complete God’s. The exclusive theological use of barah, to create, sets the original creative work of God apart from all possible human works.

Nonetheless, in Exodus 31:1-11 and 35:31-36:1 Bezalel and his fellow workers were filled with the Spirit in designing a sanctuary for the Ark of the Covenant. Some reject any general doctrine of creativity from such a specific reference to a sacred activity.[23]Yet, in the light of the portrayal of the whole creation as God’s sanctuary in Genesis 1 and humans as God’s image set in the sanctuary as a sign and sacrament of God’s rule, creative activity is one way we externalise our identity and calling in God’s image. As J.R.R. Tolkien writes, we are “sub-creators.”

Although now long-estranged,Man is not wholly lost nor wholly changed.Dis-graced he may be, yet is not de-throned,And keeps the rags of lordship he once owned:Man, Sub-Creator …

Fantasy [or any creative work] remains a human right: we make in our measure and in our derivative mode, because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker.[24]

The special and Spirit-filled callings of Bezalel and his colleagues and the Old Testament prophets (Exodus 3, Isaiah 6, Jeremiah 1:1-15) are universalised as God’s Spirit is poured out “on all flesh … even on the male and female slaves” (Joel 2:28-29), the lowest of workers. In the New Testament we are all filled, gifted and called as part of God’s prophetic people, the new humanity in Christ (Acts 2:17-18, Ephesians 4:1-13).

The Old Testament’s high view of creation, humanity and our creative calling to dominion under God (Psalm 8) prepares the way for a powerful sense of God’s providential presence in our work. Robert Banks sees Luther linking "human work with God's ongoing providential work" in Psalm 127 and 139, Proverbs 3:5-6 and Matthew 6:25-34 and 10:29-31. He says of Luther's providential extension of church-based vocation terminology that:

He has widened the notion of calling beyond its reference to evangelistic and pastoral responsibilities to cover all work that provides a service to others. As long as the special importance of the former is recognised, and the responsibility of all Christians to be involved in them,[25] Luther's more highly developed understanding of vocation is quite valid. It simply brings Paul's teaching on work into contact with broader biblical themes and through these develops it in a more systematic and practical way. [26]

Philosopher Paul Helm agrees:

So a Christian has two callings. He is effectually called by grace, converted. In addition there is a call of a different kind, that which is provided by the network of circumstance, personal relations, past history, in which he is found when God's grace comes to him .... Here the biblical teaching about divine providence is presented in a particular and personal way.[27]

As Harry Blamires notes:

The Christian doctrine of vocation ... follows indisputably from two propositions. The first, that God is everywhere active in human affairs and his will operative at all times. The second, that he is a rational God, fully aware that the world needs farmers and miners as well as priests and nuns .... The doctrine of Providence stresses the ceaseless and ubiquitous intrusion of God into human affairs. The doctrine of Vocation defines a prime mode of that intrusion.[28]

Lee Hardy pictures Luther's perspective as "God's Providential Presence in the Work of our Hands."

Through the order of stations [social roles] God sees that the daily needs of humanity are met. Through the human pursuit of vocations across the array of earthly stations the hungry are fed, the naked are clothed, the sick are healed, the ignorant are enlightened and the weak are protected. That is, by working we actually participate in God's ongoing providence for the human race.[29]

However, this had dangers through Luther’s historical and polemical over-identification of God’s providence with particular social structures and occupational roles. This sometimes led to a sense of vocational unchangeability and manipulative misuse of calling language to exploit those called by requiring long hours and paying low wages.

A Threefold, Trinitarian Calling

Luther’s great breakthrough in recognizing ordinary callings nonetheless over-emphasized God’s work as Creator and providential maintainer of creation and our work of staying in our created roles and occupations. He separated this from God’s work in Christ and the Spirit in his doctrine of God’s Two Kingdoms - the worldly kingdom of God the Creator and the heavenly kingdom of Christ and the Spirit. This split within God’s triune work opened up his doctrine of vocation to later secularization – separating our sense of calling to a job from our primary calling to Jesus.[30]

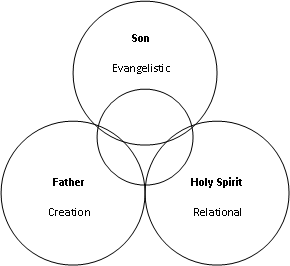

To gain a balanced and united understanding of our callings (including work) in the light of God’s work, we will draw on the Trinitarian summaries of God’s work in the great orthodox creeds (Apostles and Nicene Creeds). Because we all have partial perceptions of God’s work we need to be more thoroughly Trinitarian instead of often practicing a Unitarian (one person e.g. God as Creator) or Binitarian (two person e.g. Jesus and the Spirit) theology playing favourites with the Trinity. Individuals, institutions and marketplace ministries often grasp one or two aspects of the Trinity’s work that highlights their own work or calling. Some mainline liberal churches and groups focus more on work as just dominion over and care for creation (the Father), some Evangelicals focus on work as a means to evangelism (the Son), some Pentecostals focus on spiritual gifts, fruits and new creation (the Holy Spirit). A particular emphasis, gifting or calling is fine but it is divisive and competitive to claim ours is more essential, as if the whole body of Christ is only one organ (1 Corinthians 12:14-31).

In classical Trinitarian theology, the Father, Son and Spirit all cooperate in their work in the world. Yet each takes the lead in the Trinitarian dance for their special part in salvation history. So while the Father is primary in creation, the Word/Son is involved (John 1:1, Colossians 1:15-20, Hebrews 1:3 etc) and the Creator Spirit too (Genesis 1:2, Psalms 104: 30 ‘You created all of them by your Spirit, and you give new life to the earth’). Christ is primary in relation to reconciliation and evangelism (Matthew 28:20ff; 2 Corinthians 5:17-21), the Spirit in transformation and completion of our relationships to God (Romans 5:1-8, Matthew 22:37-40), humanity (Galatians 5, 1 Corinthians 12) and the earth (Romans 8:18-27). But they work together. Like the Trinity we should all bless each one’s work if we are to have a properly balanced view of God’s Trinitarian work in creation, reconciliation and transformation. This is why we need a three callings or commissions theology.

takes the lead in the Trinitarian dance for their special part in salvation history. So while the Father is primary in creation, the Word/Son is involved (John 1:1, Colossians 1:15-20, Hebrews 1:3 etc) and the Creator Spirit too (Genesis 1:2, Psalms 104: 30 ‘You created all of them by your Spirit, and you give new life to the earth’). Christ is primary in relation to reconciliation and evangelism (Matthew 28:20ff; 2 Corinthians 5:17-21), the Spirit in transformation and completion of our relationships to God (Romans 5:1-8, Matthew 22:37-40), humanity (Galatians 5, 1 Corinthians 12) and the earth (Romans 8:18-27). But they work together. Like the Trinity we should all bless each one’s work if we are to have a properly balanced view of God’s Trinitarian work in creation, reconciliation and transformation. This is why we need a three callings or commissions theology.

Paul Stevens similarly pictures this as a three-tiered wedding cake of callings. I will adapt this in a more explicitly Trinitarian way.[31] The foundational bottom layer of the creation commission is to all humans (to communion, community building and co- or preferably sub-creativity—Genesis 1: 26-28, Psalm 8). The second tier is the Great Commission—to all Christians (to conversion, community and Christ-like character, witness and dominion through service (Matthew 28:18-20, Ephesians 4:1-13). The third and top layer is the Spirit’s personal or particular call to individuals to apply the relational commission or Great Commandment to work, family and political roles (1 Corinthians 7:17, 20, Ephesians 5: 21-6:9, Romans 13) using their unique gifts.

This Trinitarian view of our callings in the context of the three commissions corrects the Medieval Catholic hierarchical distortion of only some Christians i.e. monastics and priests, having a Christian and personal calling. A Protestant echo of this has clergy and missionaries on top as working for Christ as pastors and evangelists,[32]caring professions like social workers and doctors next as having a personal, spiritual calling working for others in personal relationships, while business people, skilled workers, scientists, IT technicians, artists etc. who develop creation or matter come last.

Each of these Trinitarian emphases has real strengths, but also weaknesses, when used exclusively. Their exclusive emphasis leaves us with an unbalanced, wobbly one or two-legged stool which cannot take the weight of our working lives and cause misunderstanding, disunity and competition in workplace ministry.

Firstly, mainline Christians with a creational/cultural commission emphasis rightly stress the biblical wisdom tradition that we are creatures first,then Christians, and stress our positive relationship to the world of nature and culture. They have made great contributions to science, culture and social justice. As just one example of many, Professor Graeme Clark, inventor of the bionic ear, consciously imitated God’s creative design of a shell he found on a beach to thread electrodes to stimulate hearing in the similarly spiral-shaped human ear.[33]

Many leave out the realm of our relationship with creation and the earth in blessing, dominion and stewardship (Genesis 1:26-28, 2 and Psalm 8). The creation commission is often the Great Omission compared with the Great Evangelistic Commission and the Great or Love Commandment. The sense of its foundational greatness, as wide as creation, has been lost. The loss of the creation commission has detrimental pastoral effects on Christians who are not primarily or directly people-workers or evangelistic workers. They often feel like third-class believers because they are not social workers or evangelists at work.

Yet an exclusive or over-emphasis on God as Father and Creator can become easily secularised and lose a sense of evangelistic urgency and Christ’s finality and uniqueness in a comfortable chaplaincy to secular, pluralistic societies and workplaces. This over-emphasis can also lack a sense of the Spirit’s intimate and intrusive involvement in our life and work in creation.

The modern secularised and individualised Protestant ethic distortion often depicts calling as just an individual career, forgetting the divine Caller and Gifter and other relational priorities. A thoroughly Trinitarian approach to calling does not anchor it to a static, deistic view of nature, but sees the Son and the Spirit thoroughly involved with the Father in calling us to humbly co-operate in the work of creation and re-creation.

Secondly, Evangelicals (like myself) are rightly Christ-centred and urgently evangelistic, majoring on the calling of the Great Commission. But they forget that Christ is also the creator as John 1, Colossians 1:15-20 and the first chapter of almost every NT book shows. They stress the urgency of training more ‘‘fulltime Christian workers” for kingdom work and see ordinary or secular work as worthwhile only “to put food on the table and money in the plate” or people in the kingdom through evangelism. They fail to recognise that exercising responsible dominion through work is also kingdom work. Dominion or ruling is what kings do. Ruling creation is worthwhile in itself not merely as a means to evangelism. It is worship of the King of all creation (Romans 12: 1, 2).

Many still identify real Christians with clergy and missionaries called away from ordinary, creation work by Christ’s call to evangelistic or Kingdom work. I recently heard a well-known, gifted preacher in a prominent US church make a throw-away remark about the dirty, smelly fishing trade Jesus called his disciples from. The distaste smacked of a man of letters, a pastor (like myself) who works with words and people, not creation or things, completely overlooking the necessary, useful, and rewarding nature of the work itself.

An antidote to such an over-emphasis on Christ’s call to evangelise is the story that former Institute of Christian Studies lecturer Calvin Seerveld tells about his Dutch father and fishmonger. One day a woman asked for some fish. His father sprang into action and speedily and skilfully gutted and scaled it. The pleased customer said “I can see that you haven’t missed your calling.”[34]

Recently, I ate swordfish in a fine Gloucester (Massachusetts) restaurant while watching a fishing boat unloading its catch. I also saw a wonderful monument there to those thousands “that go down to the sea in ships” (Psalms 107:23) and who risked and lost their lives. I then read the book and saw the movie The Perfect Storm about many of them. I vowed never to take the fish I eat or the people who catch and prepare it for granted again. Theirs is a difficult, but still divine calling of exercising respectful dominion over the sea.

Because the three persons of the Trinity work co-operatively, not competitively, we need to re-link the creation and evangelistic commissions. The creation commission’s go forth and ‘fill the earth’ (Genesis 1:28 to Adam, cf. Genesis 9:7 to Noah, Genesis 12:1-3 to Abram) is behind the Great Commission’s ‘go’ into the world (Matthew 28:18-20 or ‘as you go’ about your daily work and life (Matthew 10:7).When Jesus says ‘all authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me’ he claims dominion over all creation as the true, ultimate human[35]

Thirdly, others from a more Pentecostal perspective correctly remind us of the importance of the Holy Spirit’s presence, calling, gifting, empowering and healing, anticipating the Kingdom’s coming. People are gifted by God’s Spirit (Ephesians 4:1-13; Romans 12:3-8) for specific tasks for others’ good (1 Corinthians 14:12). The Spirit also applies the relational commission of love for God and others to our particular relational roles and responsibilities. The Holy Spirit nurtures the fruit of Christlike character (Galatians 5:22-26) that is developed in our life and work callings.

The Holy Spirit’s calling of all God’s gifted people makes us all 24/7 servants or full-time ministers (1 Corinthians 12:5). Even Nero’s Roman state is called God’s “minister” or “servant” (Romans 13:4 before Nero lost his philosopher – adviser Seneca and his sanity). We are all kleros or "called" (from which “clergy” derives), and all are laos or "people" (from which "laity" or "God’s people" derives).[36]Given the Spirit’s pouring out upon all believers at Pentecost (Acts 2:4, 17-18), we need to rediscover our calling to the priesthood, prophethood and kingship of all believers, teaching/pastoring, prophetically challenging and wisely ruling/managing God’s people and creation respectively (Jeremiah 18:18). Bank manager Sandra Herron rediscovered this by ‘Reflecting Christ in the Banking Industry: The Manager as Prophet, Priest, and King.”[37]To affirm these gifts and callings of God’s people like Sandra we need to develop forms of recognition of lay vocation in society through regular lay or marketplace commissioning services.[38]

However, those who over-stress the Spirit’s work can forget that the Spirit is the Spirit of the Word/Christ and of the Creator.[39]Thus they rightly pray for spiritual healing in church, but not often for the work of doctors and nurses[40]or architects, builders and craftspersons (Exodus 35:2-3; 1 Chronicles 28:11-12) in the workplace who also have God’s creative gifts. But gifts of administration, craftsmanship, mercy, evangelism, political leadership and counsel etc overflow the church to bless the workplace. Miroslav Volf, who comes from a Pentecostal background, contrasts the traditional “additive” or top-up model of new supernatural and extraordinary spiritual gifts being added to our ordinary created talents with a more biblical “interaction” model that sees the integral relationship between created and re-created gifts, both coming from God’s creative and re-creative Spirit.[41]

A recent debate in LayNet magazine revealed the difficulty many preachers and people have in associating spiritual gifts and calling with created things or matter. A bishop wondered how a truck-driver could possibly have any sense of calling, not being a professional people-person like a doctor, nurse or social worker who is supposed to love others according to the Great Commandment. However, philosopher-priest-carpenter Armand Larive notes how the Hebrew word hokmah is used for wisdom and skill. Bezalel, “chosen [or called] by God and …filled with the Spirit of God, with skill, ability and knowledge in all kinds of crafts” (Exodus 35:30 cf. 35) and other craftsmen working on the tabernacle have it, “taking and respectfully using what the created order will allow. A goldsmith knows the malleability of his material, a farmer knows the seasons, a sailor [or fisherman] develops an eye for the seasons and stars. It would apply also to the way a truck driver can back a big rig into a narrow alley. Such a driver has hokmah.”[42] This is an expression of the creation commission of having responsible dominion over the earth or material reality, but the Creator Spirit (Genesis 1:2, Psalm 104) gives the ability to do so.

While truck driving can no doubt have many monotonous elements, it also involves skill and responsibility for safety. Recently I was moving home and was shocked to find (a 10 or more ton) interstate semi-trailer arrive at my new apartment block which has a 3 ton limit on trucks entering. I warned the driver as I had when they were loading but he insisted on backing his skill. With many people watching and me pretending to have nothing to do with it, I watched as the truck got stuck half-way around a very tight bend. I had images of it being permanently stuck, blocking the apartment complex forever. Fortunately, while lacking wisdom for trying it at all, the truck-driver had the great skill to reverse the semi out, something I, who have trouble reversing a tiny trailer, could only marvel at. I thanked God in a silent prayer for this man’s dominion over machinery and matter. He had hokmah, at least over his truck.[43]

Such work exercising dominion over material creation can be not only a matter of skill but of loving care. As the Australian cartoonist Michael Leunig said:

I watched a man making a pavement in Melbourne in a busy city street: the concrete was poured and he had his little trowel and there was traffic roaring around, there were cranes and machines going, and this man was on his hands and knees lovingly making a beautiful little corner on the kerb. That’s a sort of love …. That man’s job is important and he’s a bit of a hero for doing it like that…. Love involves that as much as it involves what happens between people. It’s about one’s relationship between oneself and the world and its people and its creatures and its plants, its ideas.[44]

What Leunig calls heroic and important, Christians can see as God’s calling.

Vocational Guidance: Does God Guide People into their Work and if so How?

How does a biblical view of calling apply to an individual’s gifting from God? As we will see, this may or may not neatly fit a person’s paid work and primary use of time, particularly in developing economies. Is vocational choice just a middle-class luxury when most people are stuck with whatever job is available (if any)? Is there a single particular calling God has for us and is it for life? These are questions of vocational guidance for which we propose some basic principles based on our preceding understanding of calling.

1. We need to first focus on God’s cosmic purpose or calling to the Kingdom.

This operates on a far broader canvas than the debilitating deterministic and individualistic “dot” or “bullseye” approach of “what job is God’s will for me” or “what marriage partner is God’s choice for me?” as if there is only one job or one possible spouse.[46]This bigger biblical canvas for callings puts them in second place to our primary calling to follow Christ and “seek first his Kingdom and his justice.” Then our other basic needs will be met as well (Matthew 6:33). As Robert Banks notes “The criterion for choice and change of calling then becomes: Does it point in the direction of the Kingdom?” [46]Further, our calling to God’s Kingdom community, not pursuing an individualistic career, sets self-fulfilment in the threefold context of service to God, one another and creation. Self-fulfilment is not something to anxiously seek but more a pleasant by-product of this network of right relationships or shalom.

Callings or questions of God’s “will” for work, marriage etc are significant but not ultimately significant, in contrast to Christ’s work and God’s will for the world’s salvation (1 Timothy 2:4) and God’s ethical will. Within that will we have great freedom to prayerfully and wisely choose (if we have a choice) optimal opportunities for ministry, knowing that a mistake will not cancel our salvation. This way provides a balanced Christian response between the anxiety–inducing bullseye view inspired by heavenly voices or signs and a secularised rationalism that collapses calling into just a job or career that we rationally calculate. As Os Guinness noted earlier, more important than the “what” or “where” of guidance is the “who” of our guiding Shepherd Jesus (John 10:11-15) and who we become in Christ, not what we do.

2. “Freedom in limitation.”

In a time of such surfeit of ‘choice’ for western middle-classes and “the options generation”[47]we need a longitudinal, historical perspective on these choices in the light of the prominent lines of God’s providence in our lives and through salvation and church history. The great Swiss theologian Karl Barth writes wisely of “freedom in limitation.” God calls us providentially to serve him through the liberating limitations of our place in history, stage of life, gifts and opportunities. “These are the creaturely carriers and media of the voice of God Himself.” [48] Despite the crippling consumerist illusion of infinite choice we are finite creatures, bound to time and place. Like Esther in exile under the Persians, protecting her people from genocide, God may have raised us up “for such a time as this” (Esther 4:14).

3. A Hard Call.

What of those with little choice and a hard call? Can difficult, gruelling work, a human necessity, be a calling? Take for example Graeme Marriott’s story of his callings as a father of three children and foreman at CBM Waste Management.

We are a small … company. We were into recycling but it’s not that profitable. Our attention turns to waste disposal. My job is to run the place: I organise and do some paper work. We do garbage and recycling…. There’s three guys, and we start at 3 am…. I drive the compactor for half the run, and I run at the back of the truck for the other half. I’ve been doing this for six years. I process the recycling every day. … It’s heavy manual work. There is lifting, lots of noise especially when you’re processing. Running … steep streets is physically demanding particularly in the summer …. You’ve got to get going early, and that is disruptive to family life. You work all days, all weather, even public holidays. As an essential service you can’t have time off. I like the challenge of the physical aspect: how fast and efficient can we get?

But it’s pretty mindless – smashing bottles, running behind a truck…. People ask me about my work and some see me as a bum. In some way it is an end of the road job. But it is essential and people rely on you. If we went on strike, and waste started to build up, it would be a health risk. … Recycling is more important these days, and I’m respected a bit. My daughter’s school asked me to speak to the children about recycling. These recycling issues affect us all so my role is important. I know that even if it’s sometimes hard to say, God has called me to do my job.[49]

Graeme has a grueling job, but he makes the most of it, sharing the difficult aspects around, and he takes his responsibility seriously as something from the hand of God.

4. The Need is not Necessarily the Call.

Many years ago, as an adolescent, I visited my cousin the night she died in hospital from a brain tumour. She was delirious and I was overwhelmed with compassion at such desperate need and wanted to be a doctor. But I was not gifted at maths and science and eventually channelled my compassion towards pastoral ministry where I was more suited and less likely to kill somebody, unless they mistook the Dr in front of my name for a medical doctor.

There are many needs and our finitude means we can only be in one place at one time. So we need to pay primary attention to the needs of our “nearest” neighbours – not necessarily geographical – but those we have the gifts, resources and responsibility to meet. In this light Frederick Buechner writes: “The place God calls you to is where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.”[50] God wants us each to be “a cheerful giver,” (2 Corinthians 9:7) aware that the gifts we can gladly give, are not our private possession, but God-given, to be passed on to others.

The language of adding depth to our relational roles is also used by John Schuster.[51]

Calls draw us into the depth level of whatever roles we may already have … [They] turn the insurance policy pedlars into advisors of needed financial security, grocery store employees into health and nutrition suppliers, doctors into healers, secretaries into stewards, businesspeople into entrepreneurs, bureaucrats into civil servants, writers into dreamweavers, parents into co-creators of life.

While this may sound a bit grandiose, Schuster’s point is that awareness of God’s activity in and through our ordinary roles deepens our opportunities for extraordinary love and service.

5. Community Discernment.

One of the major problems of the western approach to guidance is its individualism and unaccountability. We make up our own minds and say “Here I stand, I can do no other’ like Luther, but without his qualification that “my conscience is captive to the word of God.” Those of a more Spirit-oriented bent can hear the voices they want to hear. Luther said to those in his day “I don’t care if you swallow the Holy Spirit feathers and all” you must convince me by Scripture, tradition and sound reason. Each of these for Luther, through the rational interpretation of Scripture in the church present and past, is a communal process. The Spirit speaks but more often to us than just me. In Acts we hear of the Holy Spirit’s guidance when Paul and Barnabas were sent on mission by the church at Antioch (Acts 13:2-3) and when the Gentiles were accepted into the then largely Jewish church without onerous Jewish laws - “it seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us” (Acts 15:28). Such corporate discernment, wrestling with one another and in mutual accountability, is a good model for our vocational discernment, though there is obviously individual liberty and responsibility also.

Archbishop William Temple was right that to choose a career on selfish or individualistic grounds, without a true sense of calling, confirmed corporately, is “probably the greatest single sin any young person can commit, for it is the deliberate withdrawal from allegiance to God of the greatest part of time and strength.”[52] But the fault is as much, if not more, that of the Church which has left people to their own devices, without resources of corporate discernment and vocational guidance, unless they are considering ordained ministry.

6. Called to be More – and Less.

Gail Godwin’s novel Evensong has a character affirm the vocation of a female Episcopal priest by saying “something’s your vocation if it keeps making more of you.” It’s more than just a job but part of a “faithful, flourishing life.” While the language of passion is all-pervasive today, vocation includes, but is more than passion in the emotional sense. It is the commitment and disciplined practice of a focus for life rather than a nibbling approach to food or a channel-surfing approach to media. It is this that “keeps making more of you.” In this way vocations or callings are connected to long-term, holistic covenants in relation to our role responsibilities - to our nearest neighbours - husbands and wives, parents and children, bosses and workers, rulers and citizens.

Gregory Jones balances Godwin: “Conversely, we ought to avoid those vocations that are likely to make “less” of us, especially if in them we are likely to be ‘shrivelled’ by one or another form of sin. We can be made ‘less’ by our own temptations, by a particular mismatch between what we are doing and the gifts we have been given by God, by contingent events that overwhelm the possibilities of continuing a specific vocation, or by the corrupting practices or institutions that currently shape our vocation.” Godwin’s phrase helps orient us toward vocations that encourage a flourishing of life.

But Godwin’s phrase ‘more of you’ can be co-opted by a seductive culture of self-fulfillment… It needs to be placed next to Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s claim in The Cost of Discipleship that when Christ calls [someone] he bids him come and die.”[53]

All from Christianity Today, August 2006, pp. 73 (Baylor), 72 (CEO) and 26-31 (“Case for Kids”). Thanks to Scott Harrower for these illustrations in his unpublished Ridley College essay “Great Expectations: What does God expect from us?” 1.

Max Lucado, He Chose the Nails, (Nashville: Word, 2000).

Cited without source by Ian Barns, “Living Christianly in a World of Technology”, Part I, Zadok Papers S144, Autumn, 2006, 2

Os Guinness, The Call (Nashville: Word, 1998), 29.

Eusebius, The Proof of the Gospel, ed. and trans. W.J. Ferrar (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1981), bk. 1, chap. 8, 48-49. Eusebius was the first “Christian” emperor Constantine’s court historian in the early fourth century.

Os Guinness, The Call (Nashville: Word, 1998), 31-34.

Gordon Fee, The First Epistle to the Corinthians, New International Commentary on the New Testament (NICNT)(Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1987), 314. The broader context of 1 Corinthians shows socially and spiritually restless Corinthians desiring upward spiritual and social mobility. Paul earlier showed how their revolutionary calling or status "in Christ" crucified (1 Cor. 1:4-7, 27-30) or relativized all other calling - racial (7:24) and social status (7:26ff.). Cf. Bruce W. Winter, Seek the Welfare of the City: Christians as Benefactors and Citizens (Carlisle/Grand Rapids: Paternoster/Eerdmans, 1994), 163f.

Gordon Fee, The First Epistle to the Corinthians, New International Commentary on the New Testament (NICNT),306f. Others take the next step "circumstances," = "setting" = "calling." D.J. Schuurman, Vocation: Discerning our Callings in Life (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004), chap. 2 finds these verses clearly associate work and other ordinary roles as "callings."

Miroslav Volf, Work in the Spirit: Toward a Theology of Work (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 109f. citing C.K. Barrett, First Corinthians, Blacks New Testament Commentary (New York: Harper & Row, 1978), 169f. Contrast Luther's confusing paraphrase of v. 24 and its change from "to which" to "in which." "Remain in that calling to which you were called, that is, where you received the Gospel; and remain as you were when called .... If you are called in slavery, then remain in the slavery in which you were called" (Luther’s Works ed. J. Pelikan vol. 28 (Philadelphia/St. Louis: Concordia and Muhlenberg/Fortress, 1955-76), 45-7. Cf. NIV v. 17 which without using "calling" refers to "the place in life that the Lord assigned to him and to which God has called him" and on v. 24 to remaining "in the situation God called him to." My italics.

Os Guinness, The Call (Nashville: Word, 1998), 31.

Gordon Fee,The First Epistle to the Corinthians, New International Commentary on the New Testament (NICNT), 306f., 321f, cf. 314 and Guinness, The Call, 31. Fee does not necessarily see God calling people to become slaves for instance, but rather that once converted while in a certain social setting, even the worst like slavery, it becomes potentially a place of service and worship. However, if that potential is unable to be fulfilled and the opportunity of release from slavery becomes available, Paul encourages people to take it. See v.21 (NRSV margin and NIV). However, the NRSV translation of v. 21 seems to imply that Paul wants Christians to stay in their situation of slavery while inwardly free in Christ. Even if this is the best translation, this needs to be read in the light of Paul’s non-dualist principle that our inward mental and spiritual states are meant to be embodied externally in our social situations as far as possible (cf. Rom. 12:1,2).

Cf. Vincent L. Wimbush, Paul the Worldly Ascetic: Response to the World and self-Understanding according to 1 Corinthians 7(Macon, GA: Mercer Uni. Press, 1987), 15ff., 21: "'Remain'" did not uphold the status quo. Instead it "relativize[d] the importance of all worldly conditions and relationships. Yet ..., even the 'remaining' is relativized": those given the chance, e.g., slaves, v. 21 "can change their social condition or status without having their status with God affected." "Remaining" counters the Corinthian catchcry of refraining - changing status or withdrawing from the world to a higher "pneumatic [spiritual] Christian existence." Paul's two digressions in v. 17-24 and 29-35 clarify his principle that worldly statuses are nothing before God. Therefore we are free to live in the world, but not of it, in "spiritual ... detachment or "'inner-worldly asceticism'"(Worldly, 70) "as if" according to v. 29-31. This is because the forms, structures, institutions and concerns of this world (schema) are not evil, but transient (Worldly, 33f.).

Os Guinness, The Call (Nashville: Word, 1998), 39 ff.

Donald R. Heiges, The Christian’s Calling rev. ed. (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1984), 47-49 demonstrates the theological and structural primacy Luther gives to our calling to respond in the inner man in the context of the church to the gospel of grace and the heavenly kingdom over our calling or vocation to respond in the outer man in the context of our neighbour to the law’s command to love and serve in the earthly kingdom. Heiges cites Luther’s Small and Large Catechisms respectively in The Book of Concord, trans. and ed. T.G. Tappert (Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press, 1959), 345 and 419. However, he notes that for polemical reasons against the Roman Catholic Church, Luther had to “emphasize (even over-emphasize) the earthly callings of every Christian.”

See Miroslav Volf, Work in the Spirit, ch. 4 and Exclusion and Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity,Otherness,and Reconciliation (Nashville: Abingdon, 1996), 50-51. This also reflects the Old Testament’s emphasis on the Judean exiles settling down in Babylon, by living and working alongside the Babylonians while praying for and “seeking the welfare [“shalom”] of the city” (Jeremiah 29:4-7). It becomes a paradigm for New Testament Christians scattered or dispersed in the Gentile world. It is also an appropriate model today for God’s scattered people called to work in the world in “exile” in Babylon. Cf. Winter, Seek the Welfare of the City.

Hans Kung, On Being a Christian (London: Collins, 1975),231.

A statement by biblical scholar Jerome Murphy-O’Connor on TV for which I have no exact source.

Martin Hengel, Poverty and Riches in the Early Church (London: SCM, 1963), 27.

John Schneider, Godly Materialism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994), 143-44.

Cf. M. Volf,Work in the Spirit,(New York: Oxford University Press, 1991)78.

See Robert J. Banks,God the Worker (Sutherland, NSW: Albatross Books, 1992) for more.

John Paul II, Laborem Exercens[On Human Labor] (London: Catholic Truth Society, 1981), section 25 where the term is not used but the concept of “Work as a Sharing in the Activity of the Creator” is.

Alan Richardson, The Biblical Doctrine of Work (London: SCM, 1952), 17-18.

J. R. R. Tolkien, "On Fairy-Stories," in Tree and Leaf (Houghton Muffin, 1965), 144-45 referring to our God-given ability to create ‘A Secondary World’ (132) of story, fantasy or culture, in the broadest sense, including work.

Banks’ reference to the “special importance” of “evangelistic and pastoral ministries can be read not in any hierarchical sense but rather as universally applicable dimensions of the Great Commission and Great Commandment respectively.

R. J. Banks, “The Vocation of the Public Servant,” in his ed., Private Values and Public Policy: The Ethics of Decision Making in Government Administration (Homebush West, NSW: Lancer, 1983), 101. D. J. Schuurmann (Vocation: Discerning our Callings in Life, [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004], 33, n. 21) helpfully compares the doctrine of vocation and the doctrine of the Trinity. Both are not explicit but rather implicit and important in Scripture.

Paul Helm, The Callings: The Gospel in the World (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1987), 48:

Harry Blamires, The Will and the Way: A Study of Divine Providence and Vocation (London: SPCK, 1957), 67.

The Fabric of this World: Inquiries into Calling, Career Choice and the Design of Human Work(Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990), 45, 47.

Miroslav Volf, (Work in the Spirit: Toward a Theology of Work [New York: Oxford University Press, 1991], 105-9), Gordon R. Preece, (The Viability of the Vocation Tradition (Lewiston: Edwin Mellen, 1998] 61, 89-99) and Darrel Cosden (The Heavenly Value of Earthly Work [Milton Keynes, UK/Peabody, MA: Paternoster/Hendrickson, 2006], 45-48) while affirming of Luther’s breakthrough to emphasise the universal call of all Christians to service in the world, all critique his dualistic and conservative Two Kingdoms framework.

The Other Six Days (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999), 73-74 borrowing Klaus Bockmuehl’s image.

Os Guinness, The Call, (Nashville: Word, 1998), 31-43.

Graeme M. Clarke, Sounds from Silence, (St. Leonard’s NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2003).

Cited in R. Paul Stevens, Doing God’s Business (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2006), 20-21.

H.W. Wolff, Anthropology of the Old Testament (London: SCM Press, 1974), 164-65.

Clement’s First letter to the Corinthians (c. AD 96) has the first use of the clergy-laity distinction.

In Robert J. Banks ed. Faith Goes to Work, (Alban Institute: 1993, 80-92)

See William Diehl, “Bringing the Workplace into the Worship Place: Celebration and Education for Worldly Ministry”, in Banks, Faith Goes to Work, 148-59.

See Gen. 1:2, Ps. 104, Isa. 32, Ezek. 36-37, Rom. 8 and C.J.H. Wright, Knowing the Holy Spirit Through the Old Testament (Oxford: Monarch, 2006), esp. 13-39.

As Ecclesiasticus or Sirach 38:1-2 tells us: “Honour physicians for their services, for the Lord created them; for their gift of healing comes from the Most High” (see also down to 38:15). According to the Sixth of the 39 articles of the Church of England this apocryphal book is “read for example of life and instruction of manners,” not to “establish any doctrine.”

Volf, Work in the Spirit, 102-5, 111-22 esp. 112. For all the positive contributions he has made to workplace ministry, Os Hillman’s The 9to5 Window (Ventura CA: Regal, 2005). 8-12 still has an additive model of gifting stressing the supernatural gifts, which, of course, must not be neglected.

“Vocational Fulfillment,” LayNet (Winter 2005), 4-5 in response to Loren Mead, “Perceiving Vocation at the Margins,” LayNet (Fall 2005) who quoted the bishop.

See Richard Sennett, The Craftsman (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008) on skill-based occupations.

Caroline Jones, An Authentic Life (Sydney: ABC Books, 1998), 2-3.

See Garry Friesen, Decision Making and the Will of God (Portland OR: Multnomah, 1980), Part 2.

Faith Goes to Work,167. Cf. Banks’ emphasis on calling to the Kingdom with Tom and Christine Sine, Living on Purpose: Finding God’s Best for Your Life (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2002).

Hugh Mackay. Generations: Baby Boomers, their Parents & their Children (Pan MacMillan Australia, 1997) referring to the then 15-30 year olds.

Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics III/4 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, ET 1961), 634-36.

“Head, Hands and Heart 1, ” Lookout http://www.achea.edu.au/~studfac

Wishful Thinking: A Seeker’s ABC (Harper SanFrancisco: rev. ed., 1993) under “Calling.”

Answering Your Call: A Guide for Living Your Deepest Purpose (Berrett-Koehler Publishers Inc., San Francisco,2003), no p.

Cited unsourced in Os Guinness, The Call (Nashville: Word, 1998) 47.

L. Gregory Jones, Everyday Matters (Nashville: Abingdon, 2003), 42 citing Evensong (New York: Ballantine Books, 2000).