Numbers and Work

Bible Commentary / Produced by TOW Project

Introduction to Numbers

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsThe book of Numbers contributes significantly to our understanding and practice of work. It shows us God’s people, Israel, struggling to work in accordance with God’s purposes in challenging times. In their struggles, they experience conflicts about identity, authority, and leadership as they work their way across the wilderness toward God’s Promised Land. Most of the insight we can gain for our work comes by example, where we see what pleases God and what does not, rather than by a series of commands.

The book is called “Numbers” in English because it records a series of censuses that Moses took of the tribes of Israel. Censuses were taken to quantify the human and natural resources available for the economic and governmental affairs, including military service (Num. 1:2-3; 26:2-4), religious duties (Num. 4:2-3, 22-23), taxation (Num. 3:40-48), and agriculture (Num. 26:53-54). Effective resource allocation depends on good data. But these censuses serve as a framework for a narrative that goes beyond merely reporting the numbers. In the narratives, the statistics are often misused leading to dissent, rebellion, and social unrest. Quantitative reasoning itself is not the problem—God himself orders censuses (Num. 1:1-2). But when numerical analysis is used as a pretext for deviating from the word of the Lord, disaster follows (Num. 14:20-25). A distant echo of this manipulation of numbers as a substitute for genuine moral reasoning can be heard in today’s accounting scandals and financial crises.

Numbers takes place in that wilderness region that is neither Egypt nor the Promised Land. The Hebrew title of the book, bemidbar, is shorthand for the phrase “in the wilderness of Sinai” (Num. 1:1), which describes the main action in the book—Israel’s journey through the wilderness. The nation progresses from Sinai toward the Promised Land, concluding with Israel in the region east of the Jordan River. They came to be in this location because God’s “mighty hand” (Exod. 6:1) had liberated them from slavery in Egypt, the story told in the book of Exodus. Getting the people out of slavery was one matter; getting the slavery out of the people would prove to be quite another. In short, the book of Numbers is about life with God during the journey to the destination of his promises, a journey we as God’s people are still undertaking. From Israel’s experience in the wilderness, we find resources for challenges in our life and work today, and we can draw encouragement from God’s ever-present help.

God Numbers and Orders the Nation of Israel (Numbers 1:1-2:34)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsPrior to the Exodus, Israel had never been a nation. Israel began as the family of Abraham and Sarah and their descendants, prospered as a clan under Joseph’s leadership, but fell into bondage as an ethnic minority in Egypt. The Israelite population in Egypt grew to become nation-sized (Exod. 12:37) but, as an enslaved people, they were permitted no national institutions or organizations. They had departed Egypt as a barely organized refugee mob (Exod. 12:34-39) who now had to be organized into a functioning nation.

God directs Moses to enumerate the population (the first census, Num. 1:1-3) and create a provisional government headed by tribal leaders (Num. 1:4-16). Under God’s further direction, Moses appoints a religious order, the Levites, and equips them with resources to build the tabernacle of the covenant (Num. 1:48-54). He lays out camp housing for all the people, then regiments the men of fighting age into military echelons, and appoints commanders and officers (Num. 2:1-9). He creates a bureaucracy, delegates authority to qualified leaders, and institutes a civil judiciary and court of appeal (this is told in Exodus 18:1-27, rather than in Numbers). Before Israel can come into possession of the Promised Land (Gen. 28:15) and fulfill its mission to bless all the nations (Gen. 18:18), the nation had to be ordered effectively.

Moses’ activities of organization, leadership, governance, and resource development are closely paralleled in virtually every sector of society today—business, government, military, education, religion, nonprofits, neighborhood associations, even families. In this sense, Moses is the godfather of all managers, accountants, statisticians, economists, military officers, governors, judges, police, headmasters, community organizers, and myriad others. The detailed attention Numbers gives to organizing workers, training leaders, creating civic institutions, developing logistical capabilities, structuring defenses, and developing accounting systems suggests that God still guides and empowers the ordering, governing, resourcing, and maintaining of social structures today.

The Levites and the Work of God (Numbers 3-8)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsNumbers 3 through 8 focuses on the work of the priests and Levites. (The Levites are the tribe whose men serve as priests—to a large degree the terms are interchangeable in Numbers.) They have the essential role of mediating God’s redemption to all the people (Num. 3:40-51). Like other workers, they are enumerated and organized into work units, although they are exempted from military service (Num. 4:2-3; 22-23). It may seem that their work is singled out as higher than the work of others, as it “concerns the most holy things” (Num. 4:4). It’s true that the uniquely detailed attention given to the tent of meeting and its utensils seems to elevate the priests’ role above those of the rest of the people. But the text actually portrays how intricately their work is related to the work of all Israelites. The Levites assist all people in bringing their life and work into line with God’s law and purposes. Moreover, the work performed by the Levites in the tent is quite similar to the work of most Israelites—breaking, moving and setting up camp, kindling fire, washing linens, butchering animals, and processing grain. The emphasis, then, is on the integration of the Levites’ work with everyone else’s. Numbers pays careful attention to the priests’ work of mediating God’s presence, not because religious work is the most important occupation, but because God is the center point of every occupation.

Offering God the Products of Our Work (Numbers 4 and 7)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsThe Lord gives detailed instructions for setting up the tent of meeting, the location of his presence with Israel. The tent of meeting requires materials produced by a wide variety of workers—fine leather, blue cloth, crimson cloth, curtains, poles and frames, plates, dishes, bowls, flagons, lamp stands, snuffers, trays, oil and vessels to hold it, a golden altar, fire pans, forks, shovels, basins, and fragrant incense (Num. 4:5-15). (For a similar description, see “The Tabernacle” in Exodus 31:1-12 above.) In the course of worship, the people bring into it further products of human labor, such as offerings of drink (Num. 4:7, et al.), grain (4:16, et al.), oil (7:13 et al.), lambs and sheep (6:12, et al.), goats (7:16, et al.), and precious metals (7:25, et al.). Virtually every occupation—indeed nearly every person—in Israel is needed to make it possible to worship God in the tent of meeting.

The Levites fed their families largely with a portion of the sacrifices. These were allotted to the Levites because, unlike the other tribes, they were not given land to farm (Num. 18:18-32). The Levites did not receive sacrifices because they were holy men, but because by presiding at sacrifices, they brought everyone into a holy relation with God. The people, not the Levites, were the prime beneficiaries of the sacrifices. In fact, the sacrificial system itself was a component in Israel’s food supply system. Aside from some portions burned on the altar and the Levites’ allotment mentioned above, the main parts of the grain and animal offerings were designated for consumption by those who brought them.[1] Everyone in Israel was thus fed in part by the system. Overall, the sacrificial system did not serve to isolate a few holy things from the rest of human production, but to mediate God’s presence in the entire life and work of the nation.

Bonnie Wurzbacher on Bringing Meaning to Work (Click to watch) |

Likewise today, the products and services of all God’s people are expressions of God’s power at work in human beings, or at least they should be. The New Testament develops this theme from the Old Testament explicitly. “You are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people, in order that you may proclaim the mighty acts of him who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light” (1 Pet. 2:9). All the work we do is priestly work when it proclaims God’s goodness. The items we produce—leather and cloth, dishes and plates, construction materials, lesson plans, financial forecasts, and all the rest—are priestly items. The work we do—washing clothes, growing crops, raising children, and every other form of legitimate work—is priestly service to God. All of us are meant to ask, “How does my work reflect the goodness of God, make him visible to those who do not recognize him and serve his purposes in the world?” All believers, not just clergy, are descendants of the priests and Levites in Numbers, doing God’s work every day.

Repentance, Restitution and Reconciliation (Numbers 5:5-10)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsAn essential role of the people of God is bringing reconciliation and justice to scenes of conflict and abuse. Although the people of Israel bound themselves to obey God's commandments, they routinely fell short, as we do today. Often this took the form of mistreating other people. "When a man or a woman wrongs another, breaking faith with the Lord, that person incurs guilt" (Num. 5:6). Through the work of the Levites, God provides a means of repentance, restitution, and reconciliation in the aftermath of such wrongs. An essential element is that the guilty party not only repays the loss he or she caused, but also adds 20 percent (Num. 5:7), presumably as a way of suffering loss in sympathy with the victim. (This passage is parallel with the guilt offering described in Leviticus; see “The Workplace Significance of the Guilt Offering” in Leviticus and Work above.)

The New Testament gives a vivid example of this principle at work. When the tax collector Zacchaeus comes to salvation in Christ, he offers to pay back four times the amount he overcharged his fellow citizens. A more modern example—though not explicitly grounded in the Bible—is the growing practice of hospitals admitting mistakes, apologizing, and offering immediate financial restitution and assistance to patients and families involved.[1] But you don’t have to be a tax collector or a medical worker to make mistakes. All of us have ample opportunities to confess our mistakes and offer to make up for them, and more. It is in the workplace where much of this challenge takes place. Yet do we actually do it, or do we try to cover up our shortcomings and minimize our responsibility?

Aaron’s Blessing for the People (Numbers 6:22–27)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsOne of the chief roles of the Levites is invoking God’s blessing. God ordains these words for the priestly blessing:

The Lord bless you and keep you;

the Lord make his face to shine upon you, and be gracious to you;

the Lord lift up his countenance upon you, and give you peace. (Num. 6:24-26)

God blesses people in countless ways—spiritual, mental, emotional, and material. But the focus here is on blessing people with words. Our good words become the moment of God’s grace in the lives of people. “So they shall put my name on the Israelites, and I will bless them,” God promises (Num. 6:27).

The words we use in our places of work have the power either to bless or curse, to build up others or to tear them down. Our choice of words often has more power than we realize. The blessings in Numbers 6:24-26 declare that God will “keep” you, be “gracious” to you and give you “peace.” At work our words can “keep” another person—that is, reassure, protect, and support. “If you need help, come to me. I won’t hold it against you.” Our words can be full of grace, making the situation better than it otherwise would be. We can accept responsibility for a shared error, for example, rather than shifting the blame by minimizing our role. Our words can bring peace by restoring relationships that have been broken. “I realize that things have gone wrong between us, but I want to find a way to have a good relationship again,” for example. Of course, there are times we have to object, critique, correct, and perhaps punish others at work. Even so, we can choose whether to criticize the faulty action or whether to damn the whole person. Conversely, when others do well, we can choose to praise instead of keeping silent, despite the slight risk to our reputation or cool reserve.

Retirement from Regular Service (Numbers 8:23-26)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsTill Death Do Us Part: Is Retirement an Option Anymore?In this blog from The High Calling, David Rupert tells the story of three people wrestling with whether to retire. The short-term financial downturn is now a multi-year economic crisis. The unemployed and underemployed are all around us. And it’s affecting retirement plans. |

Numbers contains the only passage in the Bible that specifies an age limit for work. The Levites entered their service as young men who would be strong enough to erect and transport the tabernacle with all of its sacred elements. The censuses of Numbers 4 did not include names of any Levites over the age of fifty, and Numbers 8:25 specifies that at age fifty Levites must retire from their duties. In addition to the heavy lifting of the tabernacle, Levites’ job also included inspecting skin diseases closely (Lev. 13). In a time before reading glasses, virtually no one over the age of fifty would be able to see anything at close range. The point is not that fifty is a universal retirement age, but that a time comes when an aging body performs with less effectiveness at work. The process varies highly among individuals and occupations. Moses was eighty when he began his duties as Israel’s leader (Exod. 7:7).

Retirement, however, was not the end of the Levites' work. The purpose was not to remove productive workers from service, but to redirect their service in a more mature direction, given the conditions of their occupation. After retirement they could still “assist their brothers in the tent of meeting in carrying out their duties” (Num. 8:26). Sometimes, some faculties—judgment, wisdom, and insight, perhaps—may actually improve with increasing age. By “assisting their brothers,” older Levites transitioned to different ways of serving their communities. Modern notions of retirement that consist of ceasing work and devoting time exclusively to leisure are not found in the Bible.

Like the Levites, we should not seek a total cessation of meaningful work in old age. We may want or need to relinquish our positions, but our abilities and wisdom are still valuable. We may continue to serve others in our occupations by leadership in trade associations, civic organizations, boards of directors, and licensing bodies. We may consult, train, teach, or coach. We may finally have the time to serve to our fullest in church, clubs, elective office, or service organizations. We may be able to invest more time with our families, or if it is too late for that, in the lives of other children and young people. Often our most valuable new service is coaching and encouraging (blessing) younger workers (see Num. 6:24-27).

Given these possibilities, old age can be one of the most satisfying periods in a person’s life. Sadly, retirement sidelines many people just at the moment when their gifts, resources, time, experience, networks, influence, and wisdom may be most beneficial. Some choose to pursue only leisure and entertainment or simply give up on life. Others find that age-related regulations and social marginalization prevent them from working as fully as they desire. An article by Ian Rose for the BBC, "Why we lie about being retired," explores challenges people face in retirement, especially if they enter it expecting to cease working for the rest of their lives.

There is too little material in Scripture to derive a comprehensive theology of retirement. But as we age, each of us can prepare for retirement with as much, or more, care as we have prepared for work. When young, we can respect and learn from more experienced colleagues. At every age, we can work toward retirement policies and practices that are fairer and more productive for both younger and older workers.

The Challenge to Moses’ Authority (Numbers 12)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsIn Numbers 12, Moses’ brother and sister, Aaron and Miriam, try to launch a revolt against his authority. They appear to have a reasonable complaint. Moses teaches that Israelites are not to marry foreigners (Deut. 7:3), yet he himself has a foreign wife (Num. 12:1). If this complaint had been their true concern, they could have brought it to Moses or to the council of elders he had recently formed (Num. 11:16-17) for resolution. Instead, they agitate to put themselves in Moses’ place as leaders of the nation. In reality, their complaint was merely a pretext to launch a general rebellion with the aim of elevating themselves to positions of ultimate power.

God punishes them severely on Moses’ behalf. He reminds them he has chosen Moses as his representative to Israel, speaking “face to face” with Moses, and entrusts him with “all my house” (Num. 12:7-8). “Why then were you not afraid to speak against my servant Moses?” he demands (Num. 12:8). When he hears no answer, Numbers tells us that “the anger of the Lord was kindled against them” (Num. 12:9). His punishment falls first on Miriam who becomes leprous to the point of death, and Aaron begs Moses to forgive them (Num. 12:10-12). The authority of God’s chosen leader must be respected, for to rebel against such a leader is to rebel against God himself.

When We Have Grievances Against Those in Authority

God was uniquely present in Moses’ leadership. “Never since then has there arisen a prophet in Israel like Moses, whom the Lord knew face to face” (Deut. 34:10). Today’s leaders do not manifest God’s authority face to face as Moses did. Yet God commands us to respect the authority of all leaders, “for there is no authority except from God” (Romans 13:1-3). This does not mean that leaders must never be questioned, held accountable, or even replaced. It does mean that whenever we have a grievance against those in legitimate authority—as Moses was—our duty is to discern the ways in which their leadership is a manifestation of God’s authority. We are to respect them for whatever portion of God’s authority they truly bear, even as we seek to correct, limit, or even remove them from power.

A telling detail in the story is that Aaron and Miriam’s purpose was to thrust themselves into positions of power. A thirst for power can never be a legitimate motivation for rebelling against authority. If we have a grievance against our boss, our first hope should be to resolve the grievance with him or her. If the boss’s abuse of power or incompetence prevents this, our next aim would be to have him or her replaced by someone of integrity and ability. But if our purpose is to magnify our own power, then our aim is untrue, and we have even lost the standing to perceive whether the boss is acting legitimately or not. Our own cravings have made us incapable of discerning God’s authority in the situation.

When others oppose our authority

Although Moses was both powerful and in the right, he responds to the leadership challenge with gentleness and humility. "The man Moses was very humble, more so than anyone else on the face of the earth” (Num. 12:3). He remains with Aaron and Miriam throughout the episode, even when they begin to receive their deserved punishment. He intervenes with God to restore Miriam’s health, and succeeds in reducing her punishment from death to seven days banishment from camp (Num. 12:13-15). He retains them in the senior leadership of the nation.

If we are in positions of authority, we are likely to face opposition as Moses did. Assuming that we, like Moses, have come to authority legitimately, we may be offended by opposition and even recognize it as an offense against God’s purpose for us. We may well be in the right if we attempt to defend our position and defeat those who are attacking it. Yet, like Moses, we must care first for the people over whom God has placed us in authority, including those who are opposing us. They may have legitimate grievances against us, or they may be aspiring to tyranny. We may succeed in resisting them, or we may lose. We may or may or not continue in the organization, and they also may or may not continue. We may find common ground, or we may find it impossible to restore good working relationships with our opponents. Nonetheless, in every situation we have a duty of humility, meaning that we act for the good of those God has entrusted to us, even at the expense of our comfort, power, prestige, and self-image. We will know we are fulfilling this duty when we find ourselves advocating for those who oppose us, as Moses did with Miriam.

When Leadership Leads to Unpopularity (Numbers 13 and 14)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsAnother challenge to Moses’ authority arises in Numbers 13 and 14. The Lord tells Moses to send spies into the land of Canaan to prepare for the conquest. Both military and economic intelligence are to be collected, and spies are named from every tribe (Num. 13:18-20). This means the spies’ report could be used not only to plan the conquest, but also to begin discussions about allocating territory among the Israelite tribes. The spies’ report confirms that the land is very good, that “it flows with milk and honey” (Num. 13:27). However, the spies also report that “the people who live in the land are strong, and the towns are fortified and very large” (Num. 13:28). Moses and his lieutenant, Caleb, use the intelligence to plan the attack, but the spies become fearful and declare that the land cannot be conquered (Num. 13:30-32). Following the spies’ lead, the people of Israel rebel against the Lord’s plan and resolve to find a new leader to take them back to slavery in Egypt. Only Aaron, Caleb, and a young man named Joshua remain with him.

But Moses stands fast, despite the plan’s unpopularity. The people are on the verge of replacing him, yet he sticks to what the Lord has revealed to him as right. He and Aaron plead with the people to cease their rebellion, but to no avail. Finally, the Lord chastises Israel for its lack of faith and declares he will strike them with a deadly pestilence (Num. 14:5-12). By abandoning the plan, they thrust themselves into an even worse situation—imminent, utter destruction. Only Moses, steadfast in his original purpose, knows how to avert disaster. He appeals to the Lord to forgive the people, as he has done before. (We have seen in Numbers 12 how Moses is always ready to put his peoples’ welfare first, even at his own expense.) The Lord relents, but declares there are inescapable consequences for the people. None of those who joined the rebellion will be allowed to enter the Promised Land (Num. 14:20-23).

Moses’ actions demonstrate that leaders are chosen for the purpose of decisive commitment, not for blowing in the wind of popularity. Leadership can be a lonely duty, and if we are in positions of leadership, we may be severely tempted to acquiesce to popular opinion. It is true that good leaders do listen to others’ opinions. But when a leader knows the best course of action, and has tested that knowledge to the best of his or her ability, the leader has a responsibility to do what is best, not what is most popular.

In Moses’ situation, there was no doubt about the right course of action. The Lord commanded Moses to occupy the Promised Land. As we have seen, Moses himself remained humble in demeanor, but he did not waver in direction. He did not, in fact, succeed in carrying out the Lord’s command. If people will not follow, the leader cannot accomplish the mission alone. In this case, the consequence for the people was the disaster of an entire generation missing out on the land God had chosen for them. At least Moses himself did not contribute to the disaster by changing his plan in response to their opinions.

The modern era is filled with examples of leaders who did give in to popular opinion. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s capitulation to Hitler’s demands in Munich in 1938 comes readily to mind. In contrast, Abraham Lincoln became one of America’s greatest presidents by steadfastly refusing to give in to popular opinion to end the American Civil War by accepting the nation’s division. Although he had the humility to acknowledge the possibility that he might be wrong (“as God gives us to see the right”), he also had the fortitude to do what he knew was right despite enormous pressure to give in. The book Leadership on the Line by Ronald Heifetz and Martin Linsky, explores the challenge of remaining open to others’ opinions while maintaining steadfast leadership in times of challenge.[1] (For more on this episode see, "Israel Refuses to Enter the Promised Land" in Deuteronomy 1:19-45 above.)

Offering God our First Fruits (Numbers 15:20-21; 18:12-18)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsBuilding on the sacrificial system described in Numbers 4 and 7, two passages in Numbers 15 and 18 describe the offering of the first produce of labor and the land to God. In addition to the offerings described earlier, the Israelites are to offer to God “the first fruits of all that is in their land” (Num. 18:13). Because God is the sovereign in possession of all things, the entire produce of the land and people actually belong to God already. When the people bring the firstfruits to the altar, they acknowledge God’s ownership of everything, not merely what is left over after they meet their own needs. By bringing the firstfruits before making use of the rest of the increase themselves, they express respect for God’s sovereignty, as well as the urgent hope that God will bless the continuing productivity of their labor and resources.[1]

The offerings and sacrifices in Israel’s sacrificial system are different from the gifts and offerings we make today to God’s work, but the concept of giving our firstfruits to God is still applicable. By giving first to God, we acknowledge God to be the owner of everything we have. Therefore, we give him our first and best. In this way, offering our firstfruits becomes a blessing for us as it was for ancient Israel.

Reminders of the Covenant (Numbers 15:37-41)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsA short passage in Numbers 15 commands the Israelites to make fringes or tassels on the corners of their garments, with a blue cord at each corner, “so that, when you see it, you will remember all the commandments of the Lord and do them.” In work, as elsewhere, there is always the temptation to “follow the lust of your own heart and your own eyes” (Num. 15:39). In fact, the more diligently you pay attention to your work (your “eyes”), the greater the chance that things in your workplace that are not of the Lord will influence you (your “heart”). The answer is not to stop paying attention at work or to take it less seriously. Instead, it could be a good thing to plant reminders that will remind you of God and his way. It may not be tassels, but it could be a Bible that will come across your eyesight, an alarm reminding you to pray momentarily from time to time, or a symbol worn or carried in a place that will catch your attention. The purpose is not to show off for others, but to draw “your own heart” back to God. Although this is a small thing, it can have a significant effect. By doing so, “you shall remember and do all my commandments, and you shall be holy to your God” (Num. 15:40).

Moses’ Unfaithfulness at Meribah (Numbers 20:2-13)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsMoses’ moment of greatest failure came when the people of Israel resumed complaining, this time about food and water (Num. 20:1-5). Moses and Aaron decided to bring the complaint to the Lord, who commanded them to take their staff, and in the people’s presence command a rock to yield water enough for the people and their livestock (Num. 20:6-8). Moses did as the Lord instructed but added two flourishes of his own. First he rebuked the people, saying, “Listen, you rebels, shall we bring water for you out of this rock?” Then he struck the rock twice with his staff. Water poured out in abundance (Num. 20:9-11), but the Lord was extremely displeased with Moses and Aaron.

God's punishment was harsh. “Because you did not trust in me, to show my holiness before the eyes of the Israelites, therefore you shall not bring this assembly into the land that I have given them” (Num.20:12). Moses and Aaron, like all the people who rebelled against God’s plan earlier (Num. 14:22-23), will not be permitted to enter the Promised Land.

Scholarly arguments about the exact action Moses was punished for may be found in any of the general commentaries, but the text of Numbers 20:12 names the underlying offense directly, “You did not trust in me.” Moses’ leadership faltered in the crucial moment when he stopped trusting God and started acting on his own impulses.

Honoring God in leadership—as all Christian leaders in every sphere must attempt to do—is a terrifying responsibility. Whether we lead a business, a classroom, a relief organization, a household, or any other organization, we must be careful not to mistake our authority for God’s. What can we do to keep ourselves in obedience to God? Meeting regularly with an accountability (or “peer”) group, praying daily about the tasks of leadership, keeping a weekly Sabbath to rest in God’s presence, and seeking others’ perspective on God’s guidance are methods some leaders employ. Even so, the task of leading firmly while remaining wholly dependent on God is beyond human capability. If the most humble man on the face of the earth (Num. 12:3) could fail in this way, so can we. By God’s grace, even failures as great as Moses’ at Meribah, with disastrous consequences in this life, do not separate us from the ultimate fulfillment of God’s promises. Moses did not enter the Promised Land, yet the New Testament declares him “faithful in all God’s house” and reminds us of the confidence that all in God’s house have in the fulfillment of our redemption in Christ (Heb. 3:2-6).

When God Speaks through Unexpected Sources (Numbers 22-24)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsIn Numbers 22 and 23, the protagonist is not Moses but Balaam, a man residing near the path Israel was slowly taking toward the Promised Land. Although he was not an Israelite, he was a priest or prophet of the Lord. The king of Moab recognized God’s power in Balaam’s words, saying, “I know that whomever you bless is blessed, and whomever you curse is cursed.” Fearing the strength of the Israelites, the king of Moab sent emissaries asking Balaam to come to Moab and curse the Israelites to rid him of the perceived threat (Num. 22:1-6).

God informs Balaam that he has chosen Israel as a blessed nation and commands Balaam neither to go to Moab nor to curse Israel (Num. 22:12). However, after multiple embassies from the king of Moab, Balaam agrees to go to Moab. His hosts try to bribe him to curse Israel, but Balaam warns them that he will do only what the Lord commands (Num. 22:18). God seems to agree with this plan, but as Balaam rides his donkey toward Moab, an angel of the Lord blocks his way three times. The angel is invisible to Balaam, but the donkey sees the angel and turns aside each time. Balaam becomes infuriated at the donkey and begins to beat the animal with his staff. “Then the Lord opened the mouth of the donkey, and it said to Balaam, ‘What have I done to you, that you have struck me these three times?’ ” (Num. 22:28). Balaam converses with the donkey and comes to realize that the animal has perceived the Lord’s guidance far more clearly than Balaam has. Balaam’s eyes are opened; he sees the angel and receives God’s further instructions about dealing with the king of Moab. “Go with the men; but speak only what I tell you,” the Lord reminds him (Num. 22:35). Over the course of chapters 23 and 24, the king of Moab continues to entreat Balaam to curse Israel, but each time Balaam replies that the Lord declares Israel blessed. Eventually he succeeds in dissuading the king from attacking Israel (Num. 24:12-25), thus sparing Moab from immediate destruction by the hand of the Lord.

Balaam is similar to Moses because he manages to follow the Lord’s guidance despite personal failings at times. Like Moses he plays a significant role in fulfilling God’s plan to bring Israel to the Promised Land. But Balaam is also very unlike Moses and most of the other heroes of the Hebrew Bible. He is not an Israelite himself. And his primary accomplishment is to save Moab, not Israel, from destruction. For both of these reasons, the Israelites would be quite surprised to read that God spoke to Balaam as clearly and directly as to Israel’s own prophets and priests. Even more surprising—both to Israel and to Balaam himself—is that God’s guidance at the crucial moment came to him through the mouth of an animal, a lowly donkey. In two surprising ways, we see that God’s guidance comes not from the sources most favored by people, but from the sources God chooses himself. If God chooses to speak through the words of a potential enemy or even a beast of the field, we should pay attention.

The passage does not tell us that the best source of God’s guidance is necessarily foreign prophets or donkeys, but it does give us some insight about listening for God’s voice. It is easy for us to listen for God’s voice only from sources we know. This often means listening only to those people who think like we do, belong to our social circles, or speak and act like us. This may mean we never pay attention to others who would take a different position from us. It becomes easy to believe that God is telling us exactly what we already thought. Leaders often reinforce this by surrounding themselves with a narrow band of like-minded deputies and advisors. Perhaps we are more like Balaam than we would like to believe. But by God’s grace, could we somehow learn to listen to what God might be saying to us, even through people we don’t trust or sources we don’t agree with?

Land Ownership and Property Rights (Numbers 26-27; 36:1-12)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsAs time passes and demographics change, another new census is needed (Num. 26:1-4). A crucial purpose of this census is to begin developing socioeconomic structures for the new nation. Economic production and governmental organization is to be organized around tribes, with their subunits of clans and household. The land is to be divided among the clans in proportion to their population (Num. 26:52-56), and the assignment is to be made randomly. The result is that each household (extended family) receives a plot of land sufficient to support itself. Unlike in Egypt—and later, the Roman Empire and medieval Europe—land is not to be owned by a class of nobles and worked by a dispossessed class of commoners or slaves. Instead, each family owns its own means of agricultural production. Crucially, the land can never be permanently lost to the family through debt, taxation, or even voluntary sale. (See Lev. 25 for the legal protections to keep families from losing their land.) Even if one generation of a family fails at farming and falls into debt, the next generation has access to the land needed to make a living.

The census is enumerated according to male heads of tribes and clans, whose heads of households each receive an allotment. But in cases where women are the heads of households (for example, if their fathers die before receiving their allotment), the women are allowed to own land and pass it on to their descendants (Num. 27:8). This could complicate the ordering of Israel, however, because a woman might marry a man from another tribe. This would transfer the woman’s land from her father’s tribe to her husband's, weakening the social structure. In order to prevent this, the Lord decrees that although women may “marry whom they think best” (Num. 36:6), “no inheritance shall be transferred from one tribe to another” (Num. 36:9). This decree holds the rights of all people—women included—to own property and marry as they choose in balance with the need to preserve social structures. Tribes have to respect the rights of their members. Heads of household have to respect the needs of society.

In much of today’s economy, owning land is not the chief means to make a living, and social structures are not ordered around tribes and clans. Therefore, the specific regulations in Numbers and Leviticus do not apply directly today. Conditions today require different specific solutions. Wise, just, and fairly enforced laws respecting property and economic structures, individual rights, and the common good are essential in every society. According to the United Nations Development Programme, “The advancement of the rule of law at the national and international levels is essential for sustained and inclusive economic growth, sustainable development, the eradication of poverty and hunger and the full realization of all human rights and fundamental freedoms.”[1] Christians have much to contribute to the good governance of society, not only through the law but also through prayer and transformation of life. And increasingly, Christians are discovering that by working together, we can provide effective opportunities for marginalized people to gain permanent access to the resources needed to thrive economically. One example is Agros International, which is guided by a Christian “moral compass” to help poor, rural families in Latin America acquire and successfully cultivate land.[2]

Succession Planning (Numbers 27:12-23)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsBuilding a sustainable organization—in this case the nation of Israel—requires orderly transitions of authority. Without continuity, people become confused and fearful, work structures fall apart, and workers become ineffective, “like sheep without a shepherd” (Num. 27:17). Preparing a successor takes time. Poor leaders may be afraid to equip someone capable of succeeding them, but great leaders like Moses begin developing successors long before they expect to leave office. The Bible doesn’t tell us what process Moses uses to identify and prepare Joshua, except that he prays for God’s guidance (Num. 27:16). Numbers does tell us that he makes sure to publicly recognize and support Joshua and to follow the recognized procedure to confirm his authority (Num. 27:17-21).

Succession planning is the responsibility of both the current executive (like Moses) and those who exercise complementary authority (like Eleazar and the leaders of the congregation), as we see in Numbers 27:21. Institutions, whether as big as a nation or as small as a work group, need effective processes for training and succession.

Daily Offering: Praying for Others (Numbers 28 and 29)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsAlthough people make individual and family offerings at appointed times, there is also a sacrifice on behalf of the entire nation every day (Num. 28:1-8). There are additional offerings on the Sabbath (Num. 28:9-10), new moons (Num. 28:11-15), Passover (Num. 28:16-25), and the Festivals of Weeks (Num. 28:26-31), Trumpets (Num. 29:1-6), the Atonement (Num. 29:7-10), and Booths (Num. 29:12-40). Through these communal offerings, the people receive the benefits of the Lord's presence and favor even when they are not personally at worship.[1]

The Israelite sacrifice system is no longer in operation, and it is impossible to apply it directly to life and work today. But the importance of sacrificing, offering, and worshiping for the benefit of others remains (Rom. 12:1-6). Some believers—notably, certain orders of monks and nuns—spend most of their day praying for those who cannot or do not worship or pray for themselves. In our work, it would not be right to neglect our duties to pray. But in the times we do pray, we can pray for the people we work among, especially if we know no one else is praying for them. We are, after all, called to bring blessings to the world around us (Num. 6:22-27). We can certainly emulate Numbers 28:1-8 by praying on a daily basis. Praying every day, or multiple times throughout the day, seems to keep us closest to God’s presence. Faith is not only for the Sabbath.

Honoring Commitments (Numbers 30)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsChapter 30 of Numbers gives an elaborate system for determining the validity of promises, oaths and vows. The basic position, however, is simple: do what you say you will do.

When a man makes a vow to the Lord, or swears an oath to bind himself by a pledge, he shall not break his word; he shall do according to all that proceeds out of his mouth. (Num. 30:2)

Elaborations are given to handle exceptions to the rule when someone makes a promise that exceeds their authority. (The regulations in the text deal with situations where certain women are subject to the authority of particular men.) Although the exceptions are valid—you can’t enforce the promise of a person who lacks the authority to make it in the first place—when Jesus commented on this passage, he proposed a much simpler rule of thumb: don’t make promises you can’t or won’t keep (Matthew 5:33-37).

Work-related commitments tempt us to pile up elaborations, qualifications, exceptions, and justifications for not doing what we promise. No doubt many of them are reasonable, such as force majeure clauses in contracts, which excuse a party from fulfilling its obligations if prevented by court orders, natural disasters, and the like. It doesn’t stop at honoring the letter of the contract. Many agreements are made with a handshake. Sometimes there are loopholes. Can we learn to honor the intent of the agreement and not just the letter of the law? Trust is the ingredient that makes workplaces work, and trust is impossible if we promise more than we can deliver, or deliver less than we promise. This is not only a fact of life, but a command of the Lord.

Civic Planning for Levitical Towns (Numbers 35:1-5)

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsUnlike the rest of the tribes, the Levites were to live in towns scattered throughout the Promised Land where they could teach the people the law and apply it in local courts. Numbers 35:2-5 details the amount of pasture land each town should have. Measuring from the edge of town, the area for pasture was to extend outward a thousand cubits (about 1,500 feet) in each direction, east, south, west, and north.

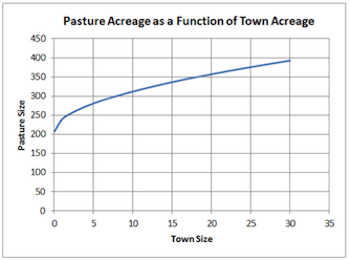

Jacob Milgrom has shown that this geographical layout was a realistic exercise in town planning.[1] The diagram shows a town with pastureland extending beyond the town diameter in each direction. As the town diameter grows and absorbs the closest pasture, additional pasture land is added so that the pasture remains 1,000 cubits beyond the town limits in each direction. (In the diagram the shaded areas remain the same size as they move outward, but the cross-hatched areas get wider as the town center gets wider.)

You shall measure, outside the town, for the east side two thousand cubits, for the south side two thousand cubits, for the west side two thousand cubits, and for the north side two thousand cubits, with the town in the middle (Num. 35:5).

Mathematically, as the town grows, so does the area of its pasture land, but at a lower rate than the area of the inhabited town center. That means the population is growing faster than agricultural area. For this to continue, agricultural productivity per square meter must increase. Each herder must supply food to more people, freeing more of the population for industrial and service jobs. This is exactly what is required for economic and cultural development. To be sure, the town planning doesn’t cause productivity to increase, but it creates a social-economic structure adapted for rising productivity. It is a remarkably sophisticated example of civic policy creating conditions for sustainable economic growth.

Mathematically, as the town grows, so does the area of its pasture land, but at a lower rate than the area of the inhabited town center. That means the population is growing faster than agricultural area. For this to continue, agricultural productivity per square meter must increase. Each herder must supply food to more people, freeing more of the population for industrial and service jobs. This is exactly what is required for economic and cultural development. To be sure, the town planning doesn’t cause productivity to increase, but it creates a social-economic structure adapted for rising productivity. It is a remarkably sophisticated example of civic policy creating conditions for sustainable economic growth.

This passage in Numbers 35:5 illustrates again the detailed attention God pays to enabling human work that sustains people and creates economic well-being. If God troubles to instruct Moses on civic planning, based on semi-geometrical growth of pastureland, doesn’t it suggest that God’s people today should vigorously pursue all the professions, crafts, arts, academics, and other disciplines that sustain and prosper communities and nations? Perhaps churches and Christians could do more to encourage and celebrate its members’ excellence in all fields of endeavor. Perhaps Christian workers could do more to become excellent at our work as a way of serving our Lord. Is there any reason to believe that excellent city planning, economics, childcare, or customer service bring less glory to God than heartfelt worship, prayer, or Bible study?

Conclusions from Numbers

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsThe book of Numbers shows God at work through Moses to order and organize the new nation of Israel. The first part of the book focuses on worship, which depends on the work of priests in conjunction with laborers from every occupation. The essential work of those who represent God’s people is not to perform rituals, but to bless all people with God’s presence and reconciling love. All of us have the opportunity to bring blessing and reconciliation through our work, whether we think of ourselves as priests or not.

The second part of the book of Numbers traces the ordering of society as the people move towards the Promised Land. Passages in Numbers can help us gain a godly perspective on contemporary work issues such as offering the fruit of our labor to God, conflict resolution, retirement, leadership, property rights, economic productivity, succession planning, social relationships, honoring our commitments, and civic planning.

Leaders in Numbers—especially Moses—provide examples of what it means both to follow God’s guidance and to fail in doing so. Leaders have to be open to wisdom from other people and from surprising sources. Yet they need to remain firm in following God’s guidance as best as they can understand it. They must be bold enough to confront kings, yet humble enough to learn from the beasts of the field. No one in the book of Numbers succeeds completely in the task, but God remains faithful to his people in their successes and in their failings. Our mistakes have real—but not eternal—negative consequences, and we look for a hope beyond ourselves for the fulfillment of God’s love for us. We see God’s Spirit guiding Moses and hear God’s promise to give the leaders who come after Moses a portion of God’s Spirit too. By this, we ourselves can be encouraged in seeking God’s guidance for the opportunities and challenges in our work. Whatever we do, we can be confident of God’s presence with us as we work, for he tells us, “I the Lord dwell among the Israelites” (Num. 35:34) in whose steps we tread.