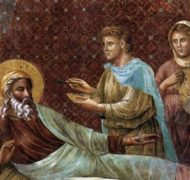

Jacob’s Unethical Procurement of Esau’s Birthright and Blessing (Genesis 25:19-34; 26:34-28:9)

Bible Commentary / Produced by TOW Project

Although it was God’s plan for Jacob to succeed Isaac (Gen. 25:23), Rebekah and Jacob’s use of deception and theft to obtain it put the family in serious jeopardy. Their unethical treatment of husband and brother in order to secure their future at the expense of trusting God resulted in a deep and long-lived alienation in the family enterprise.

God’s covenantal blessings were gifts to be received, not grasped. They carried the responsibility that they be used for others, not hoarded. This was lost on Jacob. Though Jacob had faith (unlike his brother Esau), he depended on his own abilities to secure the rights he valued. Jacob exploited hungry Esau into selling him the birthright (Gen. 25:29-34). It is good that Jacob valued the birthright, but deeply faithless for him to secure it for himself, especially in the manner he did so. Following the advice of his mother Rebekah (who also pursued right ends by wrong means), Jacob deceived his father. His life as a fugitive from the family testifies to the odious nature of his behavior.

Jacob began a long period of genuine belief in God’s covenantal promises, yet he failed to live in confidence of what God would do for him. Mature, godly people who have learned to let their faith transform their choices (and not the other way around) are in a position to serve out of their strength. Courageous and astute decisions that result in success may be rightly praised for their sheer effectiveness. But when profit comes at the expense of exploiting and deceiving others, something is wrong. Beyond the fact that unethical methods are wrong in themselves, they also may reveal the fundamental fears of those who employ them. Jacob’s relentless drive to gain benefits for himself reveals how his fears made him resistant to God’s transforming grace. To the extent we come to believe in God’s promises, we will be less inclined toward manipulating circumstances to benefit ourselves; we always need to be aware of how readily we can fool even ourselves about the purity of our motives.